- HOME

- CURRENT REVIEWS

- "WAITING FOR WALK"

- FEATURES & INTERVIEWS

- MUSIC & OUT OF TOWN REVIEWS

- RANTS & RAVINGS

- MEMORIES OF GENIUS

- H.A. EAGLEHART: HIEW'S VIEWS

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 1

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 2

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 3

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 4

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 5

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 6

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Saints & Sinners

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Pet Portraits on Commission

- COMPOSER SONATA: Hershey Felder Portraits

- TRAVIS' ANCIENT & NFS ART

- TRAVIS' PHOTOGRAPHY

- PHOTOS: FINDING MY MUSE

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: SUMMER 2024 to...

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: FALL 2023 - SPRING 2024

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: SPRING - SUMMER 2023

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: FALL 2022 - WINTER 2023

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [1946 - 1996]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [1997 - 2015]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2016 - 2018]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2019 - 2021]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2022 - 2023]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2024 to...?]

- TICKETHOLDER AWARDS 2023 - Part One

- TICKETHOLDER AWARDS 2023 - Part Two

- LA DRAMA CRITICS CIRCLE AWARDS 2023

- TRAVIS' ACTING SITE & DEMO REELS: travismichaelholder.com

- CONTACT THLA

EVERYBODY'S GOT ONE

CURRENT REVIEWS

by TRAVIS MICHAEL HOLDER

"Critics watch a battle from a high place then come down to shoot the survivors." ~ Ernest Hemingway

The Civil Twilight

Photo by Lizzy Kimball

THROUGH NOV. 24: Broadwater Studio Theatre, 1076 Lillian Way, Hollywood. http://theciviltwilight.ludus.com

[REVIEW TO COME]

Kimberly Akimbo

Photo by Joan Marcus

Pantages Theatre

Anyone who's been privy to my usual grumblings concerning the dated nature of traditional musical comedy as opposed to the innovation of contemporary musical theatre will appreciate my excitement about David Lindsay-Abaire’s multiple-Tony-winning 2021 musical adaptation of his also award-winning play Kimberly Akimbo. To me, it’s the quintessential paradigm of how such a transition should work.

Lindsay-Abaire, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 2007 for his brilliant play Rabbit Hole, once again takes us on a poignant, hilarious, deliciously inappropriate detour into the old Jerry Springer challenge to the American dream. Originating right here in ol’ LA, he received the LA Drama Critics Circle Award for Playwrighting in 2001 when the play premiered at South Coast Rep starring Marylouise Burke in the title role.

The unstoppably rule-defying playwright had first garnered both praise and vilification generated from the enormous success of his Fuddy Meers in 1999, as well as for my personal favorite of his prolific body of work, Wonder of the World, before his 16-year-old menopausal heroine Kimberly Levaco grabbed the hearts of theatregoers both here and off-Broadway—then bobbed back to LA in a sparkling return at the Victory Theatre Center directed by Maria Gobetti and starring the inimitable Judy Jean Burns, both of whom won Best honors in my TicketHolder Awards for 2007 for their work.

When it first announced that the play would be turned into a musical with Lindsay-Abaire writing the book and lyrics, and that he would be joined by two-time Tony-winning composer Jeanine Tesori (Fun Home, Caroline or Change, Thoroughly Modern Millie, Soft Power) for the project, the equally gifted worldclass artist with whom he had previously teamed for Shrek the Musical, I was sufficiently elated. And speaking of the Tonys, Kimberly Akimbo went on to win five of the little suckers, including Best Musical, Best Score, and Best Book. Now the touring company has landed back home at the Pantages and once again, it’s truly something to celebrate.

As in most of Lindsay-Abaire’s work, Kimberly Akimbo concerns the insular private world of what is on the surface just your typically dysfunctional nuclear family crashing through life circa 1999 in suburban New Jersey. Kim (a spectacular turn by Broadway star Carolee Carmello) is your classically gawky teenager dressed in costumer Sarah Laux’ Barbie-inspired finery.

She has crushes, she toils with her homework, she plays after school sports right along with everyone else, hanging out at the local “Skaters Planet” ice rink. She is typical in every way except, because of a rare genetic condition, her aging process has been accelerated five times. Although she can chew gum and navigate the ice with the best of them, Kim passed through her midlife hot flashes at age 12 and appears to now be a mature woman resolutely into her AARP years.

Even more disturbing, it will soon be her 16th birthday, which her messed-up parents have completely forgotten, and the life expectancy of those afflicted with her ailment is exactly that age. “My whole life has been later,” she laments, “and I don’t want to wait anymore.”

Not that her family seems to care much. Her mother Pattie (Dana Steingold) has problems of her own with her late-in-life pregnancy; a leg brace; battling rampant hypochondria, including the delusion that she’s dying of cancer; and recovering with bandaged hands from surgery after acquiring carpel-tunnel syndrome through years spent squeezing cream filling into pastries.

Kimberly’s alcoholic dad Buddy (Jim Hogan) isn’t much help either, breaking most promises to her while ending up “face down in a bowl of peanuts somewhere” each night after his shift as an attendant in a gas station kiosk. Beyond the obviously warped family dynamics (“Hey, we’re not perfect, okay?” offers Pattie defensively in the understatement of the century), there’s also a murky secret involving the Levacos’ sudden relocation from Lodi to Bergen County.

Kim has two allies in her homeless ex-con Aunt Debra (the show-stopping Emily Koch), who stays alive by sleeping and giving handjobs in the public library, and a moonstruck fellow student named Seth (Miguel Gil), a kid who sees only a beautiful young girl despite the fact that Kimberly looks like a little akin to Margo when they took her out of Shangri-La. Still, both of these characters have their own agendas: Debra wanting to use her niece and her gullible classmates as part of a scheme to cash checks stolen from a mailbox she’s carted to the Levacos’ basement through the streets and Seth because Kim might be the first person to ever see him as an actual person and not the school’s resident nerd.

Tony-nominated director Jessica Stone and choreographer Danny Mefford obviously possess the perfect offbeat sense of humor to understand and enhance the quirkiness of this darkly rich material; it’s a match made in Theatrical Cracker Family Heaven. And there's something quite nostalgic and comfortably old-fashioned about David Zinn's set design, which resorts to rolling pieces and descending flats rather than resorting to today's overused penchant to turn all musical theatre scenery into a series of projections.

Carmello is indelible in the leading role, finding not only the youth and latent valleygirlisms of her doomed character but gently suggesting the heartache Kimberly chokes down on a daily basis is more because her parents seem to have already given up on her than she'd controlled by her disease and the prospect of nearing her early demise. Steingold, Hogan, and Gil play their exaggerated and challenging supporting roles with great conviction, finding touching moments of humanity lurking within the demands presented by playing Lindsay-Abaire’s outrageous characters.

There’s also a clever addition to the original story, a four-person chorus featuring Kimberly’s lovestuck schoolmates who exist in a kind of sweet who-loves-whom limbo reminiscent of the starcrossed lovers from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. All four—Grace Capeless, Skye Alysse Friedman, Darron Hayes, and especially the charmingly dorky Pierce Wheeler, who moves a bit like a teenage Ray Bolger as the Scarecrow looking for a brain—are an enormous asset to the storyline and bring continuous smiles to every musical number they enhance.

Perhaps the biggest kudos, however, go to Koch, who offers a wildly unfiltered relative-from-hell so nuts the family moved without leaving a forwarding address. She is a continuous treat and vocally, she slays every opportunity to belt out her version of Miss Hannigan played by Mama Rose. But then, all the voices here are high-powered, especially when given the opportunity to take full advantage of Tesori’s infectious score.

Above everything else that makes this musical retelling of a great play so special is the fascinatingly askew signature vision of its creator, who proves here he can also writes lyrics that somehow signal the clever tongue-in-cheek and often Carlin-esque wisdom of that late-great musical theatre god Stephen Sondheim himself. Who else but Sir Steve and Lindsay-Abaire could conjure rhyming “twist” with “narcissist”?

Beyond even the success of his timelessly spot-on Kimberly Akimbo, David Lindsay-Abaire has taken on the eternal subject of family in the body of his work and finds a way to meld his gloriously goofy humor with a kind of modernday Ibsen or Miller-esque exploration into the heart of what is subtly but systematically destroying our species. His greatest insight is always finding some random breeze of hope to filter into what seems to be a bleak future for our fugged-up society, one overpowered by so much media hype and skewed politics that we all tend to overlook what is most important in our lives: each other.

THROUGH NOV. 3: Pantages Theatre, 6233 Hollywood Blvd., Hollywood. 800.982.2787 or broadwayinhollywood.com

Photo by Cooper Bates

Fountain Theatre

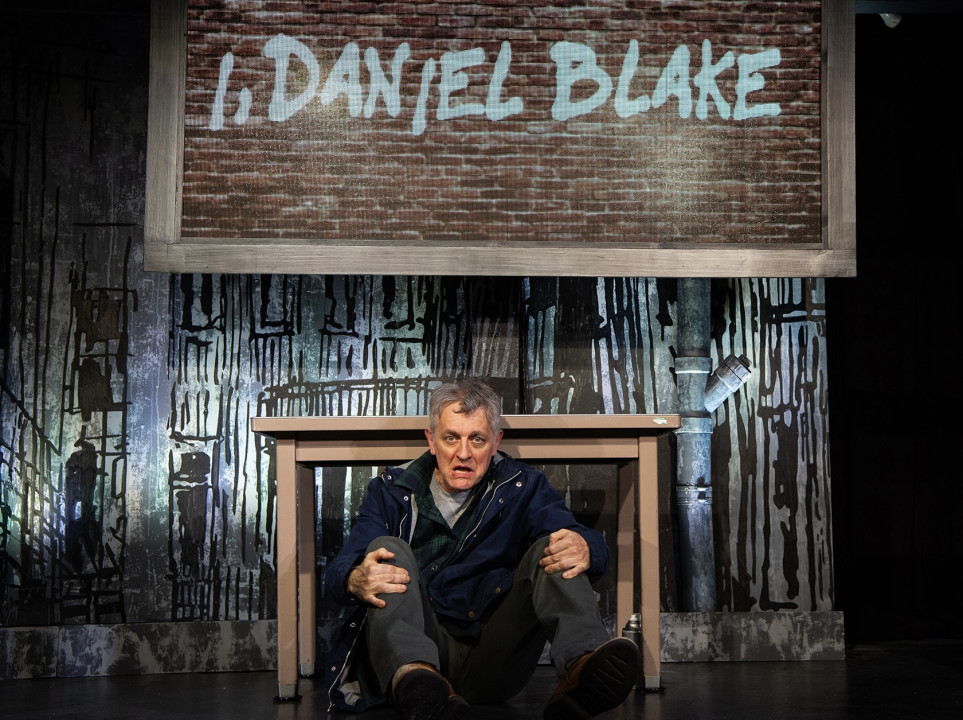

The groundbreaking Fountain Theatre, currently represented off-Broadway with their transplanted smash hit Fatherland, has given us another socially conscious “ode to the working class,” as I, Daniel Blake’s director and 32-year producing director of the complex Simon Levy commented.

Adapted for the stage from the 2016 British film by Dave Johns, who played the leading role in the Palme d’Or and BAFTA award-winning movie, I, Daniel Blake tells the woebegone tale of a hard-working middleaged carpenter from Newcastle in northeast England who, after a heart attack, is deemed unable to work.

The play follows Daniel (played by the indomitable JD Cullum) as he tries desperately to navigate the bleak and heartless public help institutions in an effort to keep food on the table and a roof over his head. As dysfunctional as our country’s own governmental social system may be, I venture to guess his agonizing Kafkaesque journey through endless paperwork, hours of hold time, and dealing with insensitive employees who obviously couldn’t care less, is even more soul-crushing than our own.

The incredibly gifted Cullum is heartbreaking as this innocent victim pushed to drastic measures to survive as he simultaneously strives to help a displaced young mother and her teenage daughter (Philicia Saunders and Makara Gamble) facing their own struggles to buck the bureaucratic odds.

The production is smoothly guided and sturdily staged by Levy and, as usual, impressively designed on the Fountain’s challenging playing space. The performances are uniformly heartfelt, but sadly the play itself isn’t worthy of the attention. Although it may have worked well on film, onstage it is unrelentingly bleak, achingly predictable, and I would defy almost anyone to not foresee the ending in the first few minutes or to not guess the fate of the desperate welfare mother continuously backed into a corner.

Maybe these themes were new and unexplored to their original British audiences, but there's nothing we haven’t heard many times over. Johns’ adaptation is told in short filmic scenes that hamper the flow of the storyline, while his glaringly two-dimensional characters are given nothing cathartic for the actors to navigate and make more interesting. As hard as the supporting players try to rise above the writing, black hats vs. white hats abound and the script offers them little to explore and shape as their own.

Cullum does a remarkable job breathing real life into his character, while Saunders has the toughest time here. Except for a couple of sweet, loving, brief interactions with her daughter, she is basically left to continuously look tortured when she’s not screaming in frustration and then subsequently begging to be forgiven for her outbursts.

Aside from these limitations, Levy, his designers, and his veteran cast of dynamic actors could not be more committed to rising above the shortcomings inherent in the play itself. Gamble, who made a memorable stage debut as the granddaughter in Pasadena Playhouse’s magnificent A Little Night Music last season, once again proves herself to be a young performer to watch.

Still, as the most important and scary election in our lifetime looms ahead of us in less than three weeks, what I, Daniel Blake beautifully delivers in spite of its theatrical blemishes is a reminder of how urgently we all, like Johns’ goodhearted workingclass Everyman hero, need to join together to lift one another up from the ugliness and communal malaise threatening to destroy everything we hold most dear.

THROUGH NOV. 24: Fountain Theatre, 5060 Fountain Av., LA. 323.663.1525 or fountaintheatre.com

American Idiot

Photo by Jeff Lorch

Mark Taper Forum

Since its grand opening in 1967, Center Theatre Group’s Mark Taper Forum has been a major entity in the ever-uphill quest to increase the profile of the performing arts in our culturally maligned reclaimed desert climes, as well as quickly becoming a prototype for the regional theatre scene in America.

When CTG announced the indefinite closure of the Taper in August of 2023, it took the breath away for us all, especially considering the massive loss of theatres big and small across the country unable to recoup after the pandemic decimated so many art institutions everywhere.

When it was announced last April that the Taper would be reopening this month, it was as though our entire community sent out a clarion call into the atmosphere above the El Lay smog like the Whos of Whoville singing and dancing around their holiday-challenged community Crissmiss tree.

Then to discover the reopening presentation would be yet another grand collaboration between CTG and Deaf West Theatre, once again featuring both deaf and hearing performers, and that it would be a massive reworking of Green Day’s extremely successful Tony-winning 2009 musical adaptation of American Idiot, their pioneering 2004 concept album of the same name, all in the world seemed slightly less discouraging.

As the icing on the cake, it was also announced that the production would also mark the CTG directorial debut of Snehal Desai, who became the third ever artistic director of the beleaguered organization in 2023, and that our town’s own treasured veteran musical director/composer David O would be at the podium—and the keyboards—to rock the helloutta the newly revitalized Taper.

One familiar Green Day song title included in American idiot itself immediately reflected my reaction to all this good news: “Wake Me Up When September Ends.”

A lot was on the line for both the theatre and Desai, but it was hard to imagine the production would not be a celebration. Deaf West has reimagined what theatre could mean for the deaf community, especially having the cajones to believe the already award-winning company could venture into the world of musical theatre.

It all started in 2000 when Deaf West was moving from its grubby original venue in East Hollywood to their new home in North Hollywood and inaugurated the space with the unheard of opening of their first reinvented musical, their spectacular Jeff Calhoun-led mounting of Lionel Bart’s classic Oliver!, where all roles were double-cast with both deaf actors signing and their counterparts speaking and singing. It was pure magic.

The following year, Calhoun returned again to helm a phenomenal presentation of Roger Miller’s Huck Finn musical Big River, which transferred first to the Taper and then reopened on Broadway in 2003, garnering a nomination for Best Revival of a Musical. That collaboration with CTG led to a highly acclaimed revival at the Taper of Pippin in 2009 and in 2015, the company’s reinvention of Spring Awakening transferred from downtown’s Inner-City Arts to the Wallis before heading off to Broadway and multiple Tony nominations.

And now, there’s a spectacular new addition to the company’s success. May I just say this in-your-face CTG/Deaf West version of American Idiot is to me the best production to hit any LA stage this year. As I told David O’s lovely wife Michele East, our seat-mate on opening night, I hope she’s ready for a return to New York next year (where David led the orchestra of Billy Crystal’s Mr. Saturday Night in 2022). I can’t imagine a world where this production does not move on to the Great White Way and once again take the town by storm.

Desai’s staging on Takeshi Kata’s three-tiered industrial-inspired set is brilliant, chockfull of unwavering visual splendor and complimented by a design team sure to win many awards, including dazzlingly bold lighting and costuming designed by, respectively, Karyn D. Lawrence and Lena Sands, and featuring welcomingly loud rocking sound by Cricket S. Myers that shakes the 739-seat Taper as never before.

The wildly talented ensemble cast made up of equal numbers of deaf and speaking performers is led by Deaf West superstar Daniel Durant (Troy Katsur’s son in the Oscar-winning Coda) as a miscreant shower-challenged young adult whose dysfunctional life is revealed in Green Day’s “Jesus of Suburbia.” Johnny is an unfulfilled and jaded kid from a broken home on his way off to try to tackle the big city, with former Disney teen star Milo Manheim along for the ride as his voice and shadow, and the uber-talented Mason Alexander Park (Desire in Netflix’ The Sandman) contributing a show-stopping turn as Johnny’s drug-induced alter-ego St. Jimmy.

The storyline features Johnny’s two besties (Otis Jones IV, voiced by James Olivas, and Landen Gonzales, voiced by Brady Fitz), local kids also more than ready to abandon the boring confines of Jingletown, USA, and attempt to shake off their disillusionment with how adults have fucked up our country and its once-honorable mission in the world.

The trio manages to screw things up just as expected, including Johnny’s downward spiral from party drugs to heroin and back again, the unexpected pregnancy of Will’s girlfriend (Ali Fumiko Whitney), and Tunny’s decision to join the military with disastrous results.

The premise is certainly slim and glaringly predictable, making American Idiot less a musical and more a concert-like song cycle built around Green Day’s classic tunes, but when it’s mounted as opulently and cleverly done as it is here, it matters not.

A lot of the praise must be heaped on choreographer Jennifer Weber, who impressively showcases the worldclass troupe of dancers—half of whom are deaf, mind you—and David O, who leads a knockout rock orchestra that could play any arena in the civilized world.

Also admirable is the barrage of a constant video word salad created by David Murikami featuring Billie Joe Armstrong’s gritty yet almost Parnassian lyrics projected on the set as the songs unfold. As someone who spent my young adult years earning my living in the “Golden Era” of the music business in the late 60s and the 70s, it’s interesting how many times I hear people today say the now legendary stars of those fine days were the last true poets and how sad it is the music has devolved so drastically over the ensuing years.

Let me tell you: the advent in the 1990s of artists such as Armstrong and the enduring message of Green Day’s socially conscious music makes American Idiot timelier than ever. Unlike so many of the artists of "back then" who have recently left us, I feel grateful to still be around a half-century later to appreciate this event, something I believe will one day be recognized as one of the most innovative and groundbreaking productions of 2024.

THROUGH NOV. 16: Mark Taper Forum, 135 N. Grand Av., LA. 213.628.2772 or CenterTheatreGroup.org

Blood/Love: A Vampire Rock Popera

Photo by Times 10

The Crimson

Just in time for Halloween, Blood/Love, subtitled A Vampire Rock Popera, has taken over the ground floor of the historic space adjacent to the Bourbon Room on Hollywood Boulevard and transformed it into a mad gothic nightclub renamed The Crimson. It's the quintessential place to give revelers past the trick or treating and school carnival age a chance to celebrate what to me is our most exciting and anticipated holiday.

First presented in October of 2023 at another historic venue, The Howard Theatre in Oshkosh, Blood/Love is the lovechild of actor, singer, musician, writer, composer, producer, and the show’s star Carey Sharpe. Obviously a major overachiever, Sharpe left a successful career as a pediatric nurse to reopen the shuttered former men’s-only Eagles Club in her hometown she then restored, renamed for her grandfather, and turned into a performing arts space featuring, besides a theatre, a rentable ballroom for weddings and events as well as an in-house bowling alley (well, it is Wisconsin).

After producing several musicals there, Sharpe decided she wanted to create her own unique entertainment, fusing her love for vampire lore, pop music, spirited choreography, and nightlife into one immersive experience. After a long successful run at the Howard, the production moved onto a sold-out engagement at Manhattan’s Public Theatre before deciding Hollywood was the perfect place for the next phase of its expansion.

Co-written by Sharpe with Dru DeCaro, Blood/Love begins in The Crimson’s new imaginatively appointed cocktail lounge before the audience enters the intimate playing space where the action unfolds all around you, followed by a moonlit DJ-led afterparty in what they’d dubbed The Atrium directly behind the theatre.

The plot revolves around a centuries-old bride of Satan (played by Sharpe, who also doubles impressively on the electric violin) who has been condemned to wander the earth with her two equally weary comrades (The Voice season 20 winner Cam Anthony and co-composer Erin Boehme), living on the blood of humans she desperately longs to become. When she meets and falls in love with a mortal musical superstar (Brennin Hunt, Roger in the 2019 live television presentation of RENT), her life changes—but only briefly when she learns her new love has made a pact of his own, exchanging his soul for superstardom.

Granted, the story is slim, but what Blood/Love features in buckets (seasonal reference intended) is an impressive score by Sharpe and DeCaro, with additional tunes from costar Boehme and Adam “Snake” Kobylarz.

Rocking the venue with 25 songs that shake the walls and featuring knockout choreography by Jonathan and Oksana Platero (DWTS and SYTYCD alum), inventive staging by director Daniel DeClaire, and highly impressive design elements, this is an evening out that could become an annual Halloween event in my crazy and eclectic ‘hood, that charmingly dysfunctional place we affectionately call Hollyweird.

Although for me Kevin Flasza’s sound could use a little adjustment in the intimate space and maybe 19 songs instead of 25 could prove to be a tad less repetitious, this production is wildly and lavishly produced, with incredible costuming designed by Michael Ngo and moodily atmospheric lighting by Tom Sutherland. There’s no doubt, however, that it’s the knockout score and performances by the uniformly fine-voiced ensemble that cast (again, intended) the show's magical conjuring spell.

Sharpe, Boehme, and Hunt have spectacular vocal skills, although it’s Anthony who steals every scene he’s in and should have twice the solo numbers he’s given. Still, the showstopping moment for me was a brilliant and jaw-droppingly acrobatic pas de deux choreographed and performed by the Plateros, perfectly showcasing the talents of two of the most gifted artists in their field working today.

For me, the only thing missing might be a little well-placed blood and gore, particularly at Halloween when it’s so much a part of any vampire story—although considering the close proximity of the audience to the action, perhaps the creators might need a resident drycleaner if that was added. As is, with at least two dancers (including Oksana Platero) sporting hair so long it slapped a couple of fellow performers and one audience member across the face during production numbers, economy of movement might have warranted some readjustment after opening night.

Is Blood/Love the next Hamilton? Well, no. But with its spectacular score, masterly singers and musicians (especially Daniel Cursio and co-composer DeCaro on bass and guitar), and some truly innovative craft cocktails to bring on even more holiday cheer, this could be the best way to spend the fun spooky month ahead.

THROUGH NOV. 2: The Crimson, 6356 Hollywood Blvd., Hollywood. www.bloodlove.com

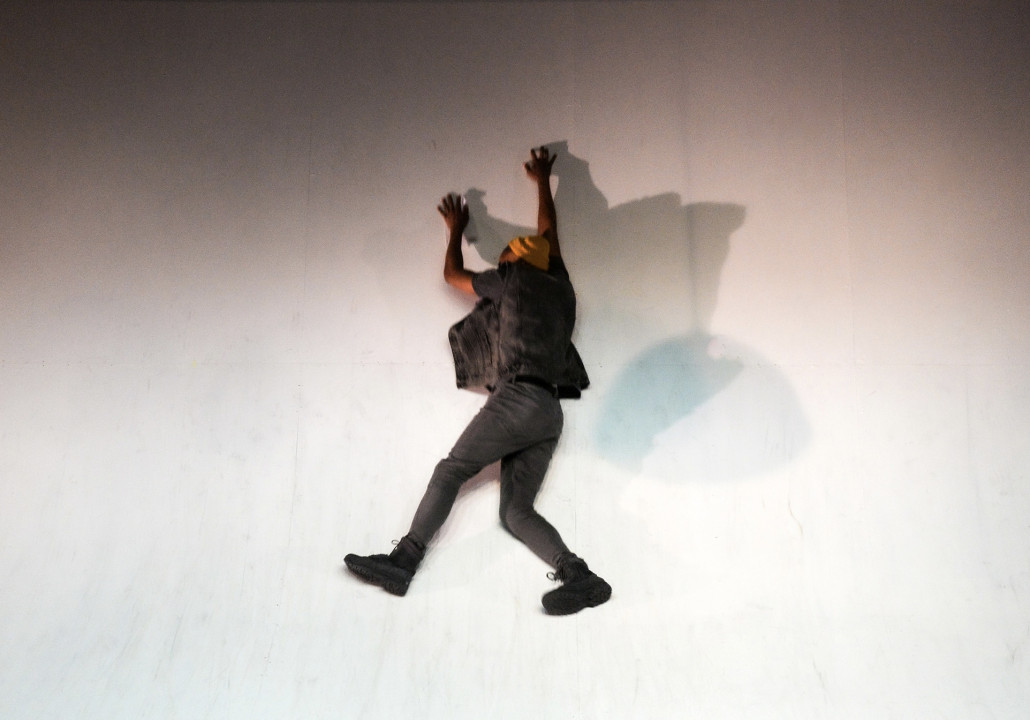

Kill Move Paradise

Photo by Cooper Bates

Odyssey Theatre Ensemble

Even before James Ijames received the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for Fat Ham, his phenomenal contemporary retelling of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the playwright was paying his unique brand of streetwise homage to Sartre’s No Exit, Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, and several similar episodes of The Twilight Zone with his 2017 play Kill Move Paradise.

Developed in 2016 under the mentorship of Chay Yew for Chicago’s Victory Gardens Theatre and first presented the following year by the National Black Theatre of Harlem, KMP emerged with a bang five years before the huge success of Fat Ham.

Ijames’ prophetically in-your-face earlier work cries out to us about the current horrendous epidemic of ongoing brutality perpetrated against innocent and unarmed African-American men and women—especially by members of what is ironically still called “law enforcement.”

One by one, four young Black men are dropped from a huge chute into a kind of nondescript afterlife waiting room, recent victims of violence stemming from racial injustice who arrive at this ominous destination without rhyme or reason, left on their own to figure out for themselves that they are indeed no longer among the living.

There are no clues where they have (literally) landed except an old computer printer doubling for a teletype machine on one side of the stage pumping out an endless list—a list, the waiting room’s first inhabitant Isa (Ulato Sam) soon discovers, of our country's real-life victims of lethal violence over the past few years.

As Isa almost accusatorially recites each name directly to the audience, many on the list are names we all should shudder to remember, including George Floyd, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and Trayvon Martin. This unfathomable pattern of death by cop inspired Ijames to write this play and its message couldn't be more urgent to be heard, even if sometimes it seems protesting such injustice is a dead-end that never seems to go away.

The promise of Ijames is all over the place here, something akin to hearing hints of familiar musical strains from West Side Story wafting briefly in passages from Bernstein’s much earlier score for On the Town.

Still, there's something measurably formulaic about KMP, a sense that we’ve heard these arguments and indictments about the public’s apathy before, a feeling that the creators are preaching to the choir—especially when the actors often come to the edge of the stage to shout out to us, asking if we’re scared of them or demanding to know why we’re just sitting there staring at them instead of doing something about the situation.

Seated directly front row center, I haven’t felt so embarrassingly Caucasian in a long time.

This sentiment echoes the complaints many of the lionhearted and radically upstart contemporary theatre companies proclaim about dealing with the older white audience base who in general would rather be watching something less personally accusatory—a fact all-too glaringly apparent considering the theatre community’s ongoing post-pandemic struggle to keep the doors open.

This play made it clear when it first premiered the kind of urban poet Ijames was about to become but KMP doesn’t have the adroitness and seasoning to more cleverly finesse Ijames’ message his later masterpiece possesses. Luckily, what this production does have to camouflage its rough edges is the incredibly visionary Gregg T. Daniels in the director’s chair.

Daniels keeps the play moving when the dialogue does not, delivering a dynamically kinetic 80 minutes of nonstop action, gloriously assisted by choreographer Toran Xavier Moore, as well as extraordinary lighting and sound created by Donny Jackson and David Gonzalez, respectively, and featuring a cast so obviously trusting and on the same page that the production breaks free of all predictability.

Sam is a powerhouse as Isa, easily commanding the stage at the play’s beginning when for an extended period of time he is the only inhabitant of this sterile and unadorned limboland.

Jonathan P. Sims and Ahkei Togun are also heartbreaking as the next two souls to arrive in this hopefully pre-paradise holding cell, particularly as their characters give in totally to Moore’s astonishingly strident tribal-influenced choreography while Sam chants his lamentable—and extensive—list of victims.

The most remarkable thing about these three performances is how they grow from wary, suspicious strangers to form a kind of familial brotherhood, something that becomes palpable when the last of the group arrives: a young boy (in a staggering performance by Cedric Joe) carrying a futuristic child’s water gun. As miserable as the others are about their own individual fates, how they instinctively band together to protect and care for Tiny is, aside from the Ijames’ built-in ineffaceable sense of humor, perhaps the only hopeful thing presented in the play.

As excellent—and haunting—as this production is, there’s a frustrating feeling that lingers here, an enveloping perception how sad it is these things must still be said at all. There was a long period of my adulthood when I lived in a world of my own making blind to the kind of racial and social injustice at the heart of KMP.

Until nine or so years ago when our former rotting orange nightmare of a national leader signaled the Morlocks that they were welcome to crawl out from under their rocks and be free to admit they think and believe as he does, I honestly thought my early years of perpetual activism protesting racial inequities and social injustices in our poor country had made a difference. Au contraire.

“I always say I hope this play becomes obsolete one day,” Ijames said in a 2018 interview. "That’s like a crazy thing for a playwright to say… but I hope one day that people will say we don’t need to do this play anymore because we are different. We are better. And every time I think we have reached a point where maybe this play is obsolete, it’s suddenly not. And the violence with which that reality comes to me never ceases to take my breath.

"I’m also anxious because I know, by the time this play opens and someone is sitting comfortably in those fabulous seats, perhaps sipping a glass of wine, that list will have grown. I’m anxious because by the time this play closes that list will have grown. I don’t say this to be cynical. I don’t say this to be pessimistic. I say it because, unless we really begin to look at why this is happening—structurally, psychically—we will repeat it."

It seems insane to me that currently over 40 percent of American citizens can't see the face of pure evil trying so desperately to bring back the hatred and destructiveness we’ve spent the last five years trying to erase. Help put James Ijames' Kill Move Paradise on its way to obsolescence on November 4, won't you? That ever-expanding list of names at least deserves that.

THROUGH NOV. 3: Odyssey Theatre Ensemble, 2055 N. Sepulveda Blvd., West LA. 310.477.2055 or OdysseyTheatre.com

Clarkston

Photo by Cooper Bates

Echo Theater Company

In this mess of a world we relentlessly try to navigate on a daily basis, there are two universal gifts offered us in our lives that can heal. One is art; the other is love. Samuel D. Hunter’s Clarkston is proof both are what we need to make our tenuous existence worthwhile.

Now in its west coast debut from Echo Theater and directed by the company’s artistic director Chris Fields, this austerely mounted but hauntingly beautiful production is one of the best presented in Los Angeles this year and its cast of three contributes significantly to that designation.

Hunter’s story takes place in and around a Costco located near the Snake River in Clarkston, Washington, a community named after William Clark, the explorer who in his diaries wrote about discovering the place in 1805 only a few weeks before the Lewis and Clark Expedition first laid eyes on the Pacific Ocean and ended their arduous 862-day journey.

Chris (Sean Luc Rogers) is a local kid and would-be writer trying to survive a horrendous childhood and find his way out of his restrictive dead-end life working the graveyard shift at the big-box warehouse. When he’s assigned to train Jake (Michael Sturgis), a quirky and neurotic transplant from Connecticut obviously on the run from something in his life, a clumsy and difficult start leads to a personal connection neither of them initially foresee.

Jake’s escape is an expedition of his own to find himself. The location was partially chosen because of his obsession with his distant relative William Clark’s diaries but primarily in an effort to get away from middle-class privilege and his well-meaning parents understandably concerned about his recent diagnosis with Juvenile Huntington’s Disease, a degenerative condition that will probably kill him before age 30.

Jake’s Ivy League degree from Bennington College in Post-Colonial Gender Studies isn’t much help either, something unfathomable to Chris, who in turn is desperately applying to programs to further his education and, besides jumpstarting a better life in a better place, give him some distance from his clinging meth-addicted single mother Trisha (Tasha Ames).

The script by the MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant recipient Hunter, Obie winner for A Bright New Boise and author of The Whale, is sweetly vulnerable and achingly poignant, creating an indelible portrait of two young people in need and the curative power of human bonding.

Fields’ staging is deceptively simple but his subtle visual touch is omnipresent. During blackouts, the actors don’t race offstage in the dim blue light but walk off slowly and, even in shadow light still obviously in character, first one leaving and then the other, usually exiting in opposite directions.

Before each scene, they re-enter and pull individual narrow sections of a gossamer curtain to the center of the cinderblock rear wall of the playing space. By the play’s conclusion, it has formed one intact backdrop, symbolizing an abstraction of the deepening connection between these two lost souls. It’s a small directorial choice but it’s a brilliant one.

The acting is the quintessential definition of ensemble work at its finest; if I had acting classes this semester, attending this production and having lengthy followup discussions about what these three performers accomplish together would be a class requirement.

Sturgis and Rogers (in an arresting professional stage debut) are truly wondrous to behold as Jake and Chris slowly become less wary and more trusting of each other—in many ways subtly becoming mirror images of one another’s behavioral patterns, something that often happens in great relationships.

Ames’ take on someone aching to but completely incapable of being a real mother to the son she adores is also heartbreaking, especially when it becomes obvious Trisha is never going to be strong enough to change.

As they sit on the bank of the Snake River and eventually along the majestic shores of the Pacific, Jake soothes his troubled friend by reading sections of his ancestor William Clark’s dairies written while seeing the same vista unfolding before him for the first time so many years before.

“It’s a terrible time to be alive,” Jake blurts out early in his characters’ tentative journey of his own making. “There’s nothing left to discover.”

Yet in Samuel D. Hunter’s masterwork Clarkston, Jake’s youthful cynicism is eventually proven wrong. It’s a play all about discoveries—and each one makes the case that no matter how arduous our own trek through life may prove to be, trusting another heart in search of his or her own individual ocean is always worth the effort.

THROUGH OCT. 21: Echo Theater Company at the Atwater Village Theatre, 3269 Casitas Av., LA. 747.350.8066 or www.EchoTheaterCompany.com

Topsy Turvy

Photo by Ashley Randall

Actors’ Gang Theatre

Founded by Oscar-winning film star Tim Robbins 42 years ago and still active under his continuing leadership, the Actors’ Gang has produced more than 150 plays in LA and has toured 40 states and five continents in its mission to honor the sacred heritage of live theatre by introducing unconventional new works and creating exciting reinterpretations of the ancient classics.

It’s been a little bit David Lynch, a little bit what the company calls “The Style,” and a whole lot of worshipful homage to the 15th-century traditions of Commedia dell’arte that conspire to energize the Gang and simply, nobody does it better.

Starting its journey in garages, art galleries, street corners, and late night takeovers of small venues, the company's unswerving search for theatrical windmills has never wavered—that is until the pandemic put a major obstacle in their path as they strive to create, educate, and inspire through their art.

Although the Gang members continued to try to adapt their workshops and educational outreach programs to online formats, Robbins could not shake the sense that something vital was missing. From that came Topsy Turvy (A Musical Greek Vaudeville), now world premiering at the Gang’s theatre for a limited run before heading off to the Sibiu International Theatre Festival in Romania, certainly with more international tour dates to follow.

Written and directed by Robbins—his 15th original play to debut at his theatre since 1982–the roots of Topsy Turvy sprout both from classic Greek theatre and the deliciously lowbrow tenets of burlesque.

As the unity of a 10-person modern Greek chorus is upended due to a widespread pandemic that keeps them from being able to meet in person, they turn to the gods—you know, the old ones with names like Dionysus and Aphrodite—to seek their wisdom and help mend the divisiveness in their ranks destroying their ability to harmonize.

Explains Robbins of his inspiration: “What was missing was what theatre reliably provides, a place of gathering and community. The Gang could not meet in its shared space… and for some, there was something tragic and wrong about their theatre being closed, something ominous and unsettling about gathering places all around the world being shuttered.”

The result is Topsy Turvy, limning that overwhelming sense of loss many of us are still experiencing four years later. It is one of the earliest theatrical responses to the experience that took such a huge chunk out of our lives and as so, presented in the usual-unusual modus operandi for which the Gang has become known, nothing and no one is left without a voice, from the unnerved members of the chorus to the gods themselves.

Robbins also strikingly directs his latest international-bound project, leading a wildly game cast of zanies who are, as always, fearless in their willingness to go beyond the bounds of any restraint in creating their characters, this fearlessness the outcome of working together in the Gang’s rule-challenging ongoing workshops.

The members of the chorus searching to “find the virtue in loneliness” are each distinctive, presumably developed from being given the freedom to bring their individual roles to life from the first gasp of artistic birth. And together, their musical moments are also quite impressive.

Although a musical director is not officially credited, I would suspect another Robbins, brother David Robbins, who has created, performed, arranged, and designed the sound for many of the troupe’s productions since 1985 (even contributing improvised musical accompaniment for the Gang’s workshops), should be acknowledged here for helping the chorus find their perfect harmonies.

The talent must run in the family as sister Adele Robbins, herself a 30-year member of the company, is an eager member of the chorus here and, aside from writing and directing Topsy Turvy, the overachieving Tim has also composed six exceptionally evocative songs and lyrics for his “musical vaudeville.”

As the summoned gods who interrupt the frustrated members of the chorus in danger of losing their moxie and no longer able to "find meaning in distraction,” Luis Quintana and Scott Harris are special standouts as the Vegas lounge-like comedy team of Cupid and Bacchus, the latter gleefully noting that since the lockdown began there’s never been a time when wine has been more appreciated.

Harris also proves his versatility doubling in the more serious role of the Biblical character Onan and as Dionysus, arriving to blast our species for the systematic destruction of our planet—and prompting a chorus member to point out that “all the gods seem so grouchy.”

Perhaps the most chilling indictments of human behavior which has directly caused the Topsy Turvy nature of our world we live in comes from Guebri Van Over as Aphrodite and a dynamic showstopping turn by Stephanie Galindo as Aztec goddess Coatlique, who accuses us all of our planet’s impending destruction and near distinction of our Native American ancestors.

Quintana, back as aptly named Barnum-esque master of ceremonies Distracto, leads a raucous troupe of street-style carnival magicians, hypnotists, and particularly Megan Stogner as a wonderfully entertaining monkey anxious to escape from her cage. All contribute to bring welcome comic relief to lighten up the proceedings between the sharply accusatory monologues by gods and others shaming our species for the rampant disregard of our planet and the responsibility of creating a “society in chaos, a society that has lost its sense of up and down.”

If there’s anything to criticize in this impressive and freshly innovative production, it might only be a sense that, between the circus-like comedic interludes, the harsh diatribes delivered to the audience by the gods begin to feel a bit like too much sermonizing. I believe this is only something noteworthy here in Topsy Turvy’s Los Angeles debut where, especially considering the general hipness of the Actors’ Gang devoted audiences, the issues raised seem to be preaching to the choir.

Robbins notes that the themes and warnings present in his latest opus are “intended as a catalyst for a conversation” and I kept thinking as it was unfolding how much its message will resonate, educate, and in a way apologize to the participants of the Romanian Sibiu Festival and to audiences anywhere it will subsequently travel.

“We are living in an aftermath of disorder and disarray,” Robbins explains of his quest for windmills. “Theatre is here precisely for these times. It has the potential to unite us. It can inspire laughter, bring us songs that touch our hearts, raise difficult questions and dichotomies, remind us of our shared humanity.”

In other words, art heals—and nothing could be more potentially healing than the fiercely creative magic generated by Tim Robbins and the invincible members of the Actors’ Gang.

UPDATE: After knockin’ em dead at the Sibiu International Theatre Festival in Romania, the Malta Theater Festival in Poland, and The Csokonai National Theater in Hungary, Topsy Turvy returns home triumphant!

THROUGH NOV. 16: The Actors’ Gang, 9070 Venice Blvd., Venice. 310.838.4264 or theactorsgang.com

Crevasse

Photo by Matt Kamimura

Victory Theatre Center

In 1938, brilliant but discredited German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl came to Hollywood. Her mission was to attend per-arranged meetings with the most influential film industry executives, the same folks not interested in distributing her documentary Olympia, an epic film which commemorated the 1936 Olympics held in Berlin.

Despite the fact that her movie intentionally focused on the athletes of the Games and was purported to try to harbor peace and unity in our ever-conflicted world, particularly paying worshipful deference to our own American hero and four-time medal winner Jesse Owens, it was Riefenstahl’s personal reputation that thwarted her efforts to see her baby reach our shores.

The snub was basically the result of her infamous 1935 propaganda feature Triumph of the Will, clearly glorifying the potentially ominous events which had unfolded the year before in Nuremberg at the Nazi Party Congress, a gathering which celebrated its leader and the man who had commissioned Riefenstahl to make the film. Her Triumph des Willens chronicled a turning point for world politics attended by some 700,000 supporters of the Third Reich and Adolf Hitler—you know, that pre-Trumpian maniac who promised to Make Germany Great Again.

When her planned visit came directly on the heels of Kristallnacht and after the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League took out a full page in the Hollywood Reporter criticizing her arrival and hinting at the rumor that Riefenstahl was the mistress of der Fuhrer himself, all but one of the meetings with the studio heads was cancelled. The only executive who did not jump ship was Walt Disney, something perhaps even more notable since he was the only one of the men who was not a Jew.

We’re told that Riefenstahl wasn’t happy about this turn of events in the world premiere of playwright extraordinaire Tom Jacobson’s arresting two-hander Crevasse, now playing at the Victory Theatre Center co-produced by its director Matthew McCray in collaboration with the Victory’s founder and artistic director Maria Gobetti.

Riefenstahl (Ann Noble) didn’t much like the Faustian thought of selling her “soul for Hollywood notoriety” in the first place, but when Disney, then mainly known as the creator of that red lederhosen-wearing rodent and struggling financially to keep his cartoon studio afloat, emerged from the rubble of her visit as the only person willing to meet with her, she was ready to skedaddle right back to the Homeland.

It was her manager Ernst Jeager (Leo Marks) who persuaded her to stay, reminding his client that the “Michael Mouse Club” had more members than the Hitler Youth. Although she saw the proposed meet-and-greet as akin to a “funhouse mirror facing true reality,” she reluctantly agreed to stay.

Marks also plays Disney, as well as Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, while Noble appears as Jeager’s doomed Jewish wife Lotte and also briefly as an FBI official interrogating him. Both stunningly gifted performers send their already soaring individual recognition as two of our town’s finest actors into the stratosphere with this auspicious debut of one of Jacobson’s best and most fascinating plays.

Noble and Marks’ rapid onstage transformations between these characters and the play’s many locations are smoothly accomplished thanks to McCray’s incredibly fluid staging winding through set designer Evan Bartoletti’s series of shimmering gossamer draperies, possibly meant to subtly conjure the symbolic image of a glacial Crevasse, a deep crack in the ice that here evokes the real life moment when the cool and stiff-backed Midwestern demeanor of Walt Disney was potentially melted by the fiery and seductive ambitions of Leni Riefenthal.

Azra King-Abadi’s striking lighting, Michael Mullen’s provocative costuming, Nicholas Santiago’s clever but ghostly projections of Bambis and dwarves and bald mountains, and especially John Zalewski’s metallic Metropolis-esque sound plot, beautifully augment this bareboned but highly evocative production, while from somewhere below the expert razzle-dazzle emerges a rather scary tale of the potential selling of one’s soul and abandoning one’s ethics in return for wealth and success.

Perhaps the most shocking and frightening image I’m left with might be Marks as the milquetoast but later well-known anti-Semite Disney, sometime after Riefenstahl has asked him if he’s a “puppet of Hollywood or a real boy,” hiding behind a stuffed toy of his famous Mouse and doing his beloved creation’s signature voice while raising one plush arm at an angle as he intones “Sieg Heil.”

Hollywood is, as Tom Jacobson reminds us, a place where the creation of art and beauty is expensive—and in his Crevasse’s final tableaux, featuring Disney sitting alone under a desk lamp as he picks up the red-covered copy of Mein Kempf Riefenthal has left him, the suggestion of the abandonment of one’s ideals in the face of the profitability of pure evil could not be more disturbing.

What an ominous business model for the creation of the world’s greatest and biggest motion picture and theme park empire Hitler’s autobiographical manifesto might have been—something our current returning equally malevolent candidate for President is not at all skittish to embrace.

THROUGH OCT. 27: Victory Theatre Center, 3324 W. Victory Blvd, Burbank. 818.841.5421 or thevictorytheatrecenter.org

Unassisted Reality

El Portal Theatre

Longtime Los Angeles weatherman Fritz Coleman retired in 2020 after four decades delivering his signature uncannily cheery forecasts on a daily basis but at age 76, his new solo show Unassisted Residency, which plays once monthly at the El Portal’s intimate Monroe Forum, proves he’s still got the chops to deliver a jocular and lighthearted tsunami to his eager and most loyal fans.

Coleman began his career coming to LA to pursue his passion for standup comedy in the early 80s after first achieving success as a well-loved deejay radio personality in Buffalo, New York.

As the story goes, a producer at NBC caught his act one night at a local club and began to woo him to become a weatherman at KNBC-TV since our weather here was so consistent that he felt it needed a little on-air boost of humor to make it more interesting.

Delivering the daily forecast with a twinkle in his eye beginning in 1984 didn’t stop Coleman from continuing to chase his original dream by performing on local stages in several successful live shows, including his hilarious award-winning turn in The Reception: It’s Me, Dad! which played around town for several years to sold out houses.

Now, after leaving NBC four years ago, Coleman is back but the demographics have changed—or I might politely say… matured.

In my own case, as someone a year older than Coleman, his focus on finding the humor in aging is most welcome. In Unassisted Residency, the comedian talks about the challenges life has to offer in these, our so-called golden years, from physical deterioration to losing contemporaries on a regular basis to navigating the brave new world of technology and social media.

As his opening warmup act, the very funny and professionally self-deprecating Wendy Liebman notes, while looking out at the sea of gray hair and Hawaiian camp shirts in their audience, that Coleman chose to present his show as Sunday matinees so his target audience can shuffle our drooping derrières on home before dark.

Along the way, he also tackles subjects such as retirement communities, nonstop doctors’ appointments, incontinence, and Viagra, not to mention having grown up sucking in our parents’ omnipresent clouds of secondhand tobacco smoke and that generation’s lackadaisical attitude toward our safety and our health, all before moving on discuss to his all-new admiration for those heroic modern educators who during the pandemic had the patience to deal with zoom-teaching his grandkids.

The one thing he doesn’t talk much about is the weather—that is beyond mentioning how grateful he is that our current heat wave didn’t deter those gathered from venturing out of our caves and offering as a throwaway that one of the reasons he retired four years ago was climate change. Although he never says it, he doesn’t really have to; we get that even for someone as funny as Coleman, everyone has their limits when it comes to the potentially catastrophic future for our poor misused and abused planet.

Then when he launches into reminiscing about the amazingly incessant search for sexual gratification in our younger years (that time Stephen King once wrote when the males of the species all look at life through a spermy haze) and how that has changed since then. As a now single guy still looking for love—with some choice remarks about online dating sites—he tells a rather steamy tale about one date that proves it ain’t over ‘til it’s over, something of which I can definitely relate.

I first met Coleman in 1988 or 1989 when I did a feature interview with him as a cover story for The Tolucan (the more industry-oriented and less Evening Women’s Club-ish-pandering predecessor of the Tolucan Times).

He was gracious and charming and kept me laughing so hard back then that I couldn’t take notes fast enough, a knack he not only hasn’t lost but has sharpened considerably over the past 40 years. I couldn’t help wondering how many of the audience members at the Forum have been following him since then and for whom the topic of not-so gently aging hits home as dead-center as it did me.

This doesn’t mean you have to be 70-something to appreciate Fritz Coleman’s hilarious gift for creating homespun storytelling in his ever-extending monthly outing called Unassisted Residency.

Although my partner Hugh, who was quite literally at least three decades younger than anyone else in the audience last Sunday and is a mere 42 years my junior, laughed longer and louder than anyone else in the audience—perhaps a reaction to hearing me bitch continuously about getting old for the last 12 years?

EXTENDED to play one Sunday a month through 2025: El Portal Monroe Forum Theatre, 5269 Lankershim Blvd., NoHo. www.elportaltheatre.com/fritzcoleman.html