- HOME

- CURRENT REVIEWS

- LADCC AWARDS FINALISTS 2025

- TICKETHOLDER AWARDS 2025 - Part One

- TICKETHOLDER AWARDS 2025 - Part Two

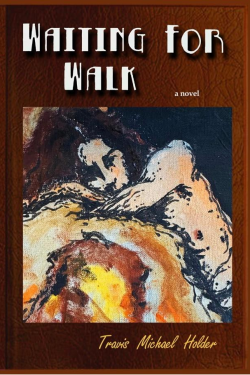

- "WAITING FOR WALK"

- TRAVIS MONOLOGUES 2025

- FEATURES & INTERVIEWS

- MUSIC & OUT OF TOWN REVIEWS

- RANTS & RAVINGS

- MEMORIES OF GENIUS

- H.A. EAGLEHART: HIEW'S VIEWS

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 1

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 2

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 3

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 4

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 5

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 6

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Saints & Sinners

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Pet Portraits on Commission

- COMPOSER SONATA: Hershey Felder Portraits

- TRAVIS' ANCIENT & NFS ART

- TRAVIS' PHOTOGRAPHY

- PHOTOS: FINDING MY MUSE

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: WINTER 2025 to... ?

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: WINTER - FALL 2025

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: SUMMER - WINTER 2024

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: FALL 2023 - SPRING 2024

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [1946 - 1996]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [1997 - 2015]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2016 - 2018]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2019 - 2021]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2022 - 2023]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2024 - 2025]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2026 to...

- TRAVIS' ACTING SITE & DEMO REELS: travismichaelholder.com

- CONTACT THLA

My quasi-memoir, or what Hershey Felder dubbed my “auto-novel,” is the story of growing up as a kid actor—with names changed to protect the innocent AND the guilty. It was written in 2005 but, totally incapable slug that I am at marketing (at least myself), it sat dormant for 17 years until social media proved more than just a place to check who's died, play Wordle, or see photos of what people are eating.

WAITING FOR WALK is available for purchase on Amazon

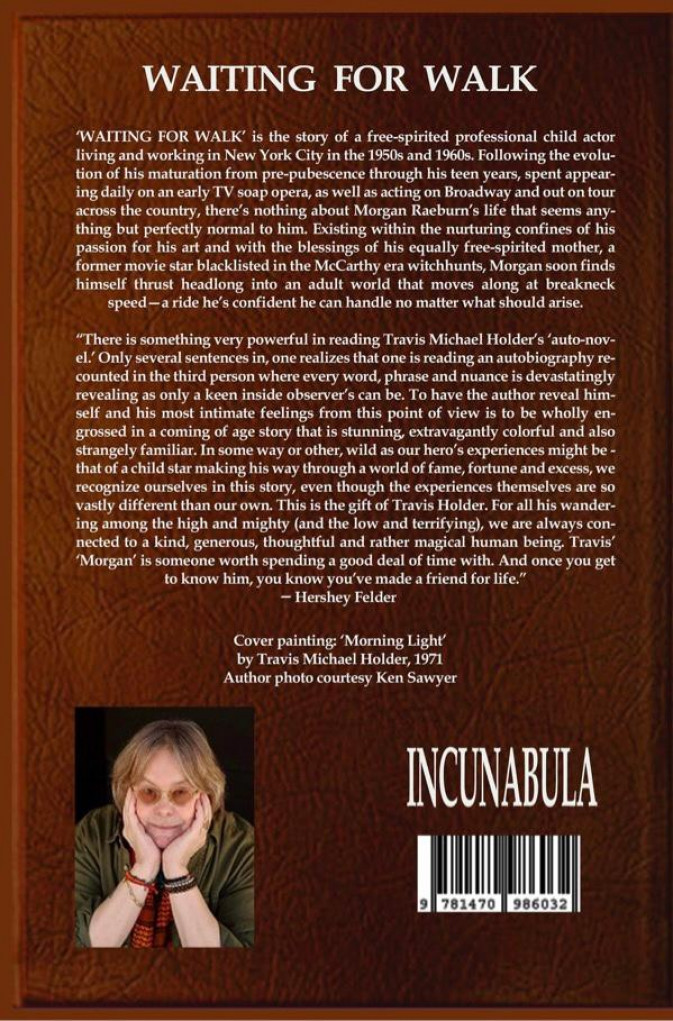

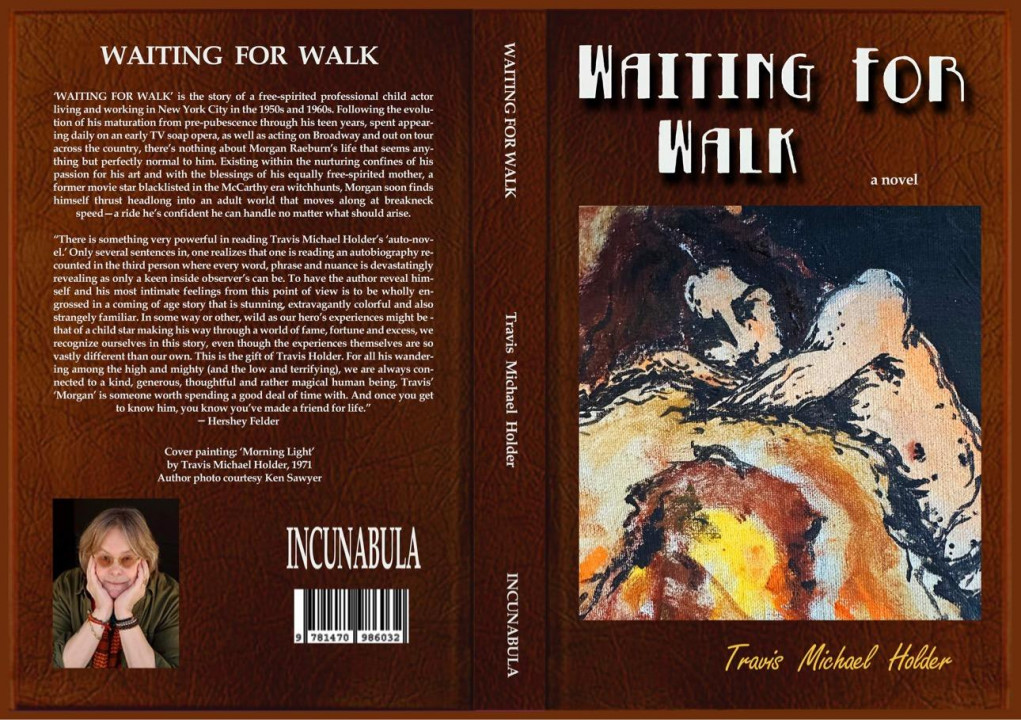

SYNOPSIS:

Waiting for Walk is the story of a free-spirited professional child actor living and working in New York City in the 1950s and 1960s. Following the evolution of his maturation from pre-pubescence through his teen years, spent appearing daily on an early TV soap opera, as well as acting on Broadway and out on tour across the country, there’s nothing about Morgan Raeburn’s life that seems anything but perfectly normal to him. Existing within the nurturing confines of his passion for his art and with the blessings of his equally free-spirited mother, a former movie star blacklisted in the McCarthy era witchhunts, Morgan soon finds himself thrust headlong into an adult world that moves along at breakneck speed—a ride he’s confident he can handle no matter what should arise. A major personal crisis at age 14 instantly proves that theory wrong, sending the rampant hormones crashing through his quickly changing body into an emotional tailspin so horrendous that Morgan’s mother reconsiders her noninterventionist parenting. After recuperating from his nightmarish sexual initiation, she moves her son back into the family’s home in a quiet suburb of Chicago so he might finish growing up in a less hazardous environment. But it’s too late for that. Morgan Raeburn somehow knows the only way he’ll survive is by continuing to make his own decisions, bucking the rules of what society thinks is acceptable and, above all, living and thinking as an artist at all costs.

Winding through Waiting for Walk are some fascinating characters, including his mother’s best friend Judith, the notoriously reclusive Hollywood legend with whom he lives on the upper Westside when his mother returns to the midwest, a balls-out kind of woman who has for years successfully hidden her live-in lesbian lover from the world. Among the questionable role models are also Christian McCarren, the dashing international movie star who becomes Morgan’s obsession and whose own obsession in return changes both of their lives forever; Mercer Andrews, the tarnished but brilliant perpetually stoned-out Southern playwright who chases him around the dressing room at every opportunity; Maggie, his female high school art teacher who helps deliver him from his trauma state, leading them into a torrid secret relationship; and Sean Lauria, the strapping though angelic actor-dancer who falls in love with Morgan but is as afraid to let the nature of his affections show. Then there’s Morgan himself, committed to honesty and enlightenment at every moment of his life, yet so desperately afraid to admit his own confusing feelings to anyone, least of all to himself.

* * *

An Excerpt from Chapter Two:

Aside from all the horror stories of sharks swimming around in the theatrical waters prowling for young pink shrimpies with their squirmy little tails, Morgan knew he had a wonderful and unique life. Even at 13, he knew he loved being onstage more than anything in the world and he was certainly more comfortable there than anywhere else in the real non-show business world.

Real life often alarmed Morgan a bit. People seemed so insincere to him when he was not working and home in Elmgrove or thrust into a situation where those around him were not the comfortable actors and artists and musicians and freaks he loved and understood so much more completely. But even considering his often commended early maturity and his uncommon exposure to all things adult, the scariest of anything he knew wasn’t jumping off a high dive or getting decent grades.

Even as a little kid in Manhattan, Morgan could get to the studio and auditions and school by himself, eat by himself, get home by himself from just about anywhere on the island. He never in his life had the time—or interest—to learn how to ride a bike or play football, but he could hail a cab with killer instinct, just like the most seasoned New York veteran. Still for all the many things he could do, including putting an audience right smackdab in the palm of his hand, that one nagging little thing continued to taunt his sense of bravado.

The thing he dreaded most was walking down the street in Manhattan by himself at the height of rush hour. Morgan never minded taking a cab or transferring on the subway, but walking alone during the day in midtown frightened the crap out of him. The problem was that he was so much smaller than most everyone else commuting around alone, and without a grown-up to hold his hand or guard him through the often dense pedestrian traffic, he could often be jostled and bumped and sent careening into street corner pretzel carts.

But standing on a corner in anticipation of the DON’T WALK sign changing to WALK was the worst thing of all. He would be on the curb facing a sea of humanity impatient for all the streaks of yellow cabs to pass and the signal to change. As Morgan stood waiting for WALK, his stomach would begin to churn. It was like that annual running of the bulls in that village in Spain or wherever, only he was heading toward the beasts rather than running away from them. The light would change and the sea of humanity on the opposite curb would start right for him, as he did in return. When the two crashing forces of ordinary people headed in opposite directions met in the middle, he could feel them all tense up, lifting their briefcases and umbrellas high in the air for safety, poised and ready as they came in for the kill. Morgan was more times than not all but trampled beneath the rushing crowds and many, many times, he would find himself right back on the same side of the street where he’d started.

Eons later, long after the death of both his mother and his first great love, Morgan would return to Manhattan from his west coast home for the first time in many years to start rehearsals for a play. He was anything but a wimpy kid at this point in his life; he was now quite an imposing adult. He smiled broadly as he faced his first midtown street corner at Fifty-seventh and Madison and its opposing troops of pedestrian wannabes.

This time out, he knew he would get to the other side.

* * *

Cover Blurb from Hershey Felder:

“There is something very powerful in reading Travis Michael Holder’s 'auto-novel.' Only several sentences in, one realizes that one is reading an autobiography recounted in the third person where every word, phrase and nuance is devastatingly revealing as only a keen inside observer’s can be. To have the author reveal himself and his most intimate feelings from this point of view is to be wholly engrossed in a coming of age story that is stunning, extravagantly colorful and also strangely familiar. In some way or other, wild as our hero’s experiences might be - that of a child star making his way through a world of fame, fortune and excess, we recognize ourselves in this story, even though the experiences themselves are so vastly different than our own. This is the gift of Travis Holder. For all his wandering among the high and mighty (and the low and terrifying), we are always connected to a kind, generous, thoughtful and rather magical human being. Travis’ 'Morgan' is someone worth spending a good deal of time with. And once you get to know him, you know you’ve made a friend for life.” — Hershey Felder

Interview with Incunabula’s Dave Mitchell, 28 NOV 22:

Incunabula recently published Travis Michael Holder’s quasi-autobiographical novel ‘Waiting For Walk’, a beautifully written account of a young man growing up in the artistic and performing community. Dave Mitchell of Incunabula conducted this conversation with him.

DM: How much stuff had your written before this book?

TMH: I’ve been writing all my life, the first being a ghost-written autobiography of our family dog when I was about age 6 called ‘My Life with the Uprights.’ Since that auspicious debut, I’ve had six plays produced nationally and my first, ‘Surprise Surprise,’ another thinly-veiled autobiographical confessional, became a feature film released in 2010 for which I co-wrote the screenplay. And then there’s the nuts-and-bolts writing. I’ve been a theatre writer and critic in Los Angeles since 1987, along the way for Back Stage and Entertainment Today, among others, and for my own website since 2017. I was told when I started reviewing theatre it would kill my acting career, but I’ve proven the naysayers wrong. I’ve been doing both for 36 years now and… gee, now that I think about it, maybe they were right after all.

DM: You’ve approached publishers with it before? What was the reaction?

TMH: Well, yes and no. See, to my embarrassment, I wrote ‘Waiting for Walk’ in 2005 during many hours of free time while out with a play. I had two publishers interested back then, but when it was completed, the first told me his partner thought there were already too many books out there written by us self-obsessed actors and the second told me she’d take it on if I could start her off with a $2,800 consultation fee. As someone good at marketing everybody but myself, I basically stuffed it a drawer and spent all these years kicking myself for being a dysfunctional shithead and not pursuing publishing it.

DM: Aside from the main character (obviously) the most memorable person in the book for me is Geraldine. Can you tell me a bit more about her?

TMH: Well, clearly she’s based on my own mother, who also died of cancer when I was 18, the same age as Morgan is when he loses his mother. And… well, here’s where the first thoughts of fictionalizing my own story began. Geri is all based on my mother until what I always call the Dreaded Chapter Five. The rape. My mother, who had always been very liberal in what she taught me about people and accepting of everyone, suddenly changed drastically — I think because she blamed herself, as Geri does in my book, for being so freewheeling with the freedom she allowed me and how she let me live my life. It was the worst period in my life. Because my father basically could no longer even look at me and my mother did nothing to stand up to him, at age fourteen I left their home and stayed with someone I thought of as my second mother, a well-known actress and Chicago philanthropist who had played my mother in a play. Geri is an amalgam of her and of my own mom from before the time she so drastically turned on me because of my possible sexual ‘awakening.’ Let me say though in defense of my mother, after that incident she spent the next — and the last — four years of her life apologizing to me for her reaction and asking for my forgiveness. I tried to convince her that I forgave her but our relationship was never the same. Even after all these years, her first reaction haunts me.

DM: The book deals with quite a few themes, including ‘coming of age’ and ‘the quest for identity’. What was your chief focus when writing this?

TMH: Ha! Truthfully I had no thought of writing an in-depth coming of age story when I started. I’ve always been a rather prolific storyteller and I had so many people along the way tell me that I should write my theatrical stories down and turn them into a memoir. I had no idea, no plan whatsoever about the direction it swept me in — but as the more personal stuff started to spill out, the book took me along with it. And I’m glad it did. For my entire life, I thought the Dreaded Chapter Five — which I would never have imagined I’d ever consider writing about — was my fault. I had convinced myself that my curiosity, my teasing him was the blame. Writing about it, especially in the third person, was revelatory to me. Incredibly cathartic. I realized then, in my friggin’ late fifties, that I was the innocent party. I cannot tell you the weight that lifted off my shoulders. Marley’s chains had nothing on me.

DM: The book has obvious significance to people belonging to the LGBTQ communities, but I believe its appeal crosses all boundaries of social inclusion/exclusion. What was your approach to that aspect when writing?

TMH: Well, I’ve been in theatre and surrounded by artistic and freethinking people all my life. I’m not sure there was really any “approach” I took when working on this. I’ve always been outspoken and unashamed, something that has gotten me in trouble more times in my life than I can tell you. See, like Morgan, the first time I was confronted by a same sex couple, I was told by my mom (the ‘before’ mom) that they were just two people in love. I had some of the same conflicts as Morgan when I was discovering who I was but honestly, my angst was far less because I had never seen such behavior as anything but normal. That aspect of the book — and moments like the encounter with the guy in the overalls on the subway, for instance — are completely my own truths.

DM: How do you feel society’s attitudes have changed (if at all) since the period when the book was set?

TMH: Oh, my god. Night and day. Or at least I thought so until 2016 when our nightmare former president gave permission for every racist and homophobic troglodyte to crawl out from under their rocks. Basically, most of what I knew about rural America was from Steinbeck novels and looking out the window from an airplane some 36,000 feet above sea level. I was rather protected from the Morlocks, always surrounded by open, creative people, so there was nothing about my life I thought I needed to keep to myself — except what happened to me in Chapter Five. Still I was raised in the 1950s when gay bars were raided and guys caught had their whole lives and careers destroyed when their names and addresses were printed in the newspaper. No, we’ve come a long, long way thanks to gay rights pioneers like Morris Kite, not to mention as a society in general thanks to Dr. King and John Lewis and Diane Nash, someone who’d became a great inspiration to me when I was active in SNCC as a young’un. Yes, lots of changes, which is what makes me desperately sad as I watch so many of the things we fought for being systematically demolished by the Trogs.

DM: Was it that device of blending your two ‘mothers’ that prompted your decision to write the book in the third person?

TMH: No, really, that was just a result, not an intention. As I said, I’ve never known when to keep my mouth shut. But that doesn’t imply that I don’t keep confidences and private matters of others to myself when I know that would be what they would want — especially people no longer around to speak for themselves. This is actually the reason I never listened when people told me I should write a book of my travels and experiences. I once said this to an amazing director named David Galligan, who was directing me in a play. I told him I simply didn’t feel comfortable writing things down that dealt with people who’d tried so hard to keep their private lives private. He said, “Write it in the third person and call it a novel.” It was right then I started “Waiting for Walk.” So many who’ve read it along the way have wanted to know the true identities of some of the characters. I say to use their own imaginations and usually they guess correctly, though I never admit to that. And also, making it a novel gave me freedom not only to tell wonderful stories but to make them a bit more entertaining than real life. You know, it’s funny. Having written it in 2005, I had to read through again after many years and I had almost forgotten some of it. Flipping through, I suddenly came across a name even I didn’t recognize. It took me well into the chapter to suddenly remember who the character represented.

DM: Next?

TMH: Well, you know I paint. I’ve been obsessed with New Orleans and painting it for several years now and I had a gallery on Royal Street in the Quarter begin featuring my New Orleans canvases and portraits of Tennessee Williams and his homes and haunts about a year before the pandemic. The lockdown closed the place for good, so I’m trying to put together a book of my art accompanied by stories of the places, of their history or sometimes my own history with them. Also, people are still telling me I must write about my years in the music business and the legendary careers I helped jumpstart, so that’s on my plate as well. This time not in the third person. I plan to take no prisoners. It’s to be called “Guest List” and there’s a great story connected with that too. I’ll have to share it with you sometime.

* * *

P.S. The publication of "W4W" is monumental in so many ways, especially since it was reading my unpublished manuscript in 2012 that made my gorgeous 22yr-old student decide he was in love with me… and Hugh and I have been together ever since!