- HOME

- CURRENT REVIEWS

- LADCC SPECIAL ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2025

- TICKETHOLDER AWARDS 2025 - Part One

- TICKETHOLDER AWARDS 2025 - Part Two

- "WAITING FOR WALK"

- TRAVIS MONOLOGUES 2025

- FEATURES & INTERVIEWS

- MUSIC & OUT OF TOWN REVIEWS

- RANTS & RAVINGS

- MEMORIES OF GENIUS

- H.A. EAGLEHART: HIEW'S VIEWS

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 1

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 2

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 3

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 4

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 5

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 6

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Saints & Sinners

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Pet Portraits on Commission

- COMPOSER SONATA: Hershey Felder Portraits

- TRAVIS' ANCIENT & NFS ART

- TRAVIS' PHOTOGRAPHY

- PHOTOS: FINDING MY MUSE

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: WINTER 2025 to... ?

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: WINTER - FALL 2025

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: SUMMER - WINTER 2024

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: FALL 2023 - SPRING 2024

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [1946 - 1996]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [1997 - 2015]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2016 - 2018]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2019 - 2021]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2022 - 2023]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2024 - 2025]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2026 to...

- LA DRAMA CRITICS CIRCLE AWARDS 2024

- TRAVIS' ACTING SITE & DEMO REELS: travismichaelholder.com

- CONTACT THLA

THE BONEYARD

TRAVIS' REVIEWS: WINTER through FALL 2025

TASTY LITTLE RABBIT at Moving Arts Theatre

For over two decades, Los Angeles-based playwright Tom Jacobson has repeatedly proven himself to be one of the most prolific innovators of all things theatrical in our too often culturally-challenged reclaimed desert. Long cherished in our community for the magical and edifying body of work he has created, there’s no doubt he would be my top choice as someone to be crowned as the Playwright Laureate of Los Angeles theatre.

With over 60 plays presented in over 100 productions in the last 20-plus years, it’s almost unconscionable that Jacobson isn’t more universally acclaimed along with such dramatists as Tom Stoppard and David Hare for continuously engaging our imaginations and our curiosity as he seamlessly blends versification with history—for him, often focusing on queer history—over the last two decades.

Many of his works blend real-world biography with his ingenious knack for speculating about what might have been, as in last year’s Crevasse, which in its world premiere at the Victory Theatre Center imagined what might have happened behind closed doors during an actual meeting between Walt Disney and controversial German film director Leni Riefenstahl, Hitler’s propagandist and rumored to have once been his lover. The production was one of the major highlights of 2024 and earned Jacobson our annual LA Drama Critic Circle Schmitt Award for Outstanding New Play.

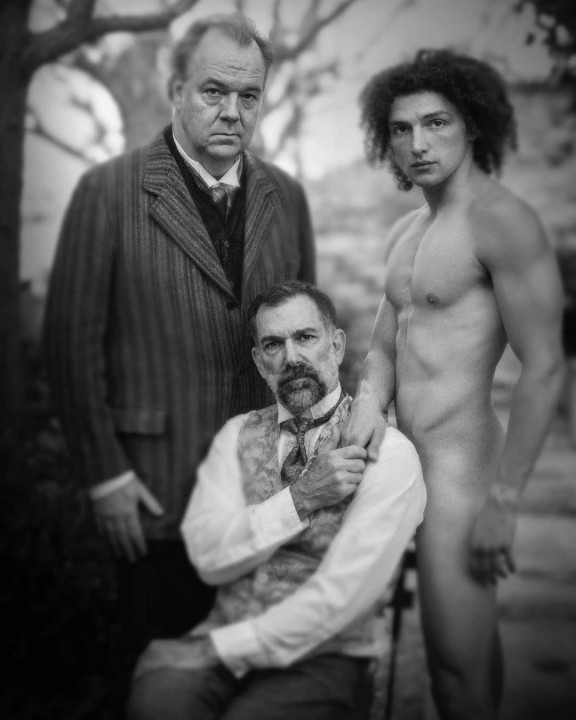

Now Jacobson returns with another riveting work, Tasty Little Rabbit, also based on historical fact and speculating about the relationship of German photographer Baron Wilhelm Von Gloeden, his main model and muse Pancrazio Buchiuni, and a mysterious visitor called Sebastian Melmoth who, without question, is in reality Oscar Wilde hiding out and trying desperately to regain his dignity after his release from prison in 1897.

Von Gloeden was one of the most prominent of the Uranian poets and artists of the time who made Taormina their home, a picturesque, sun-drenched little community perched on the seaside cliffs of eastern Sicily where they could explore their adoration for ephebic male beauty away from the narrow constrictions of conventional society.

The idyllic town’s crumbling ancient ruins and breathtaking views of Mount Etna provided a perfect backdrop for the Baron’s obsession with photographing the archetypical beauty of Sicilian young men and boys in pastoral poses recalling Greek and Italian antiquity, most often captured in the nude or wrapped seductively in togas while sporting wreaths or holding flowers that accentuated their classic looks and naturally fetching physiques.

Jacobson’s Tasty Little Rabbit winds through two time periods, from 1897 when Von Gloeden kept the local boys appreciated and their pockets filled with coinage, to the same exact spot in 1936 when Italy found itself overpowered by the censorship and cultural control of Mussolini’s Fascist regime.

LA theatrical wunderkind Rob Nagle plays both Francesco Maffiotti, an envoy of the government who arrives in that later time period to investigate the randy nature of Taormina’s past with particular focus on the decades-old photography of Von Gloeden, and he also appears in flashback as Melmoth/Wilde trying to find himself a quiet and accepting place where he can escape his past.

Robert Mammana plays Von Gloeden and also must morph in a quick light change into Cerare Acosso, the region’s stiff-backed chief magistrate who believes the Baron’s remaining photos are a blight on the good name of his community and that the remaining plates and images must be destroyed. As the conservator of the collection, Pancrazio Buchuini (Massi Pregoni), once the Baron’s lover and one of his most frequent photographic subjects, must face prosecution for his protection of the images and defiance against the customs of those restrictive modern times.

Pregoni plays Buciuni in both eras that Jacobson so fascinatingly and painstakingly explores, as a boy of 18 and also an older man of 57. This would be a Herculean task for anyone to undertake, yet this exceptional young actor easily makes it his own—something especially daunting playing opposite such dynamic and established performers as Nagle and Mammana.

Nagle is, as always, amazing in both his roles, finding a depth and import that might not have been unearthed in less talented hands. As the governmental representative, he finds a sympathy for and advocacy of Von Gloeden that he makes entirely believable despite the odds, while as Melmoth/Wilde, he successfully presents a broken, humiliated man who clearly still has not yet lost his passion for life nor his advocacy for the things in his past that so unfairly destroyed him.

Mammana is completely convincing as the inflexible bureaucrat with a secret of his own he’s fiercely trying to eradicate along with Von Gloeden’s archives, seamlessly shifting to the gentle, unapologetically hypersexualized artist whose gorgeously otherworldly yet highly naturalized artistry still mesmerizes us to this day.

Finding Pregoni, a dual citizen of both LA and Rome, to play Buciuni must have been the most exciting and defining moment for Jacobson and director George Bamber. With a face that could have been painted by Caravaggio and a body appearing to be sculpted by Michelangelo out of the finest marble, even if he couldn’t act his way out of the proverbial paper bag, he still would have been the perfect choice to cast in the role even though this character is the omphalos of the play. Serendipitously, that is certainly not the case here. Pregoni is hauntingly honest and passionate in the role, conveying with ease both the younger man’s vulnerability and the older Buciuni’s ardent defense of the preservation of his mentor’s life work.

Bamber directs with consummate skill on the tiny Moving Arts stage, never leaving his performers looking cramped or victims of the space, something perfectly accented by designer Mark Mendelson’s glorious depiction of the Sicilian countryside that instantly brought back a particularly indelible image to me: Bob Crowley’s 1998 West End design for Hare’s Judas Kiss, depicting a sweeping Mediterranean view from the veranda of a Naples hotel in yet another study of Oscar Wilde’s post-prison exile.

Dan Weingarten’s lighting helps define the shifting of time between 1897 and 1936, complete with lyrical flourishes of natural softness in the earlier era to harsher tones in the later period, both accentuated by flashes of light between them that resemble the oxygen-hydrogen fueled burst of early photography. John Zalewski’s redolent sound, Garry Lennon’s ingenious costuming that converts from one era to the other without a change, and Nicholas Santiago’s often erotically-tinged projections of some of Von Gloeden’s most familiar images, work together to create an enchanted diorama that proves you don’t always have to have an Ahmanson-sized budget to create great art.

This Tasty Little Rabbit of a play is one of the often underappreciated Tom Jacobson’s best efforts, chockfull of his love of history and the evolution of our species through what has remained behind for us to study. It is a commentary on the true nature of what constitutes art and above all, it is a declaration of how male-male love and the appreciation of its contribution to the evolution of the human experience from its earliest incarnations should be appreciated and revered for its endowment to our culture, rather than buried in shame and hypocrisy.

* * *

ADOLESCENT SALVATION from Rogue Machine at the Matrix Theatre

I’ve known playwright-on-the-rise Tim Venable since he was a young struggling actor waiting tables and not all that much older than the characters he's created in Rogue Machine’s current world premiere of Adolescent Salvation, the third of his plays debuting with the celebrated company over the last few years and the second directed by the Machine’s artistic director Guillermo Cienfuegos.

The first, debuting in 2022, was Beautiful People, featuring two disgruntled and emotionally disenfranchised suburban teenagers growing up in the 1990s who decide to risk their parents’ wrath and stay up all night on a school night in one of the boys’ basement bedrooms as they compete for top positioning in their two-person social order—and to contemplate the ultimate challenge facing young people in our increasingly mucked-up nation’s out of control gun culture.

Venable’s fast-moving first play was startlingly and horrifically real, providing a glimpse into how too many of our children have been raised in the toxic environment of contemporary American life. Now Venable has brought that kind of collective teenage angst and dysfunction into the present day where most of the issues addressed have only become more twisted and omnipresent.

Venable’s plays, at least so far, have dealt with the convoluted journey of teens and young people in America, yet they have nothing in common with the idyllic world past of Father Knows Best or Love Finds Andy Hardy. They are plays about hope and hopelessness in our dystopian society.

With proper attribution for the title as a passage from my generation’s inimitable poetess/songwriter counter-culture goddess Patti Smith in her 2010 memoir Just Kids (“I immersed myself in books and rock ‘n roll, the adolescent salvation”), Venable’s newest work of provocative contemporary art this time deals with three emotionally stunted teens having a most disastrous sleepover.

The evening has been arranged by a recently divorced alcoholic mother (Jenny Flack) so her neglected kid Natasha (a remarkable turn by Caroline Rodriguez) might be able to get out of her introverted shell and make friends with the far more socially aggressive daughter of her drinking buddy while the two mothers frequent the only accessible local bar.

Natasha isn’t all that crazy about the unexpected guest (Alexandra Lee) being thrust upon her privacy, especially since Taylor could be the definition of that familiar angry and outspoken teenage bitch supreme. Luckily, she has brought along her best friend, also named Taylor (Michael Guarasci), a sweet young gay boy who somehow manages to continually soften the continually caustic comments of his BFF.

As was the case with Venable’s second play, Baby Foot, which dealt with two other mismatched people trying to boost one another while wading through the snarl of drug rehab—I’ve only heard since I missed seeing it—Adolescent Salvation is staged in the Machine’s tiny second space above the Matrix lobby, a kind of renovated attic perfect for costume storage that has now been utilized for several highly successful productions.

The in-your-face intimacy of their 35-seat Henry Murray Stage has had magical results with the productions I’ve seen performed there, especially Sophie Swithinbank’s riveting two-person Bacon earlier this year, which actually had the smell-worthy aroma of our favorite culinary obsession wafting through the space as rashers were slowly cooked right behind the audience’s heads.

This time out, however, I think the choice of presenting Adolescent Salvation in the cramped reinvented storeroom might have been a mistake—especially during a massive heatwave on a Sunday sfternoon. What initially was certainly unique, staging yet another entire play in this space is becoming somewhat gimmicky.

The imaginative set design by Joel Daavid is incredibly visceral, depicting Natasha’s cramped and memorabilia-crowded bedroom and includes a walk through her closet beginning when entering the first floor staircase leading to the theatre upstairs. Although dodging hanging clothes and contemplating an eclectic array of teenaged treasures is absolutely ingenious, once you’re seated, it becomes more cumbersome than exciting.

The problem is the action in this minuscule playing space needs to revolve around Natasha’s bed and there’s simply not enough room to maneuver around it without making audience members have to pull in their feet and wince as sudden movement and violent action (well choreographed by Ned Mochel) unfolds too close for comfort, even if making us squirm in our seats is part of the desired effect.

Where such a thing has aided and even enhanced other productions mounted in the Murray, here it's somehow more distracting than propitious. Perhaps the “stage center” placement of two matronly overdressed and obviously shocked older ladies sitting about a foot from the bed, their reactions in full view of of the rest of the audience, exacerbated my reaction here, especially when about halfway through the performance they found it okay to start loudly whispering to one another.

The subtle performance of Rodriguez is absolutely revelatory, completely riveting in her ability to stay totally focused and in the moment no matter what the challenge, and her eleventh-hour scene with Flack as her significantly toasted mother returns home from the local Margaritaville offers the best acting and best writing in the production.

As the two Taylors, I found both actors less successful, each intent on hammerng in their characters’ individual traits in case we don’t get it. While Guarasci plays it stereotypically light-in-the-loafers, losing the dearness of what a sweetheart his Taylor really is, Lee’s sharp-tounged, eye-rolling performance is so one-note it results in not caring much about what happens to her. One last scene where her Taylor redeems herself as a potentially sympathetic friend after all comes too late and inadvertently hints at what the actor has been missing all along.

As a surprise and mostly uncredited fifth character, Keith Stevenson could really be good and actually does manage to become a sympathetic figure when his conduct should leave him to be something of a villain—although not to me personally since I’ve found myself in my life in a similar situation. Still, Stevenson’s inaudibility in his one scene is exceedingly frustrating. The Murray Stage might be crazily intimate, but lines still must be delivered with enough clarity and projection to be heard.

Still, Venable’s Adolescent Salvation is a raw, jarringly disturbing play, an unbridled view of what our fucked-up country and its plethora of self-absorbed absentee parents have done to emotionally destroy our own future generations.

We as a society have passed on a culture of misogyny and violence that has dehumanized and robotized our young, from our entertainment options that proudly boast the number of people who are blown away by gun violence to our bloviated and bigoted opinions overheard at the family dinner table while discussing our dastardly, elaborately self-destructive choices in elected officials too egocentric to consider the future of our dying planet.

Unfortunately, none of this emerges as an Orwellian science-fictionalized warning. The exceptional gifts of Tim Venable, so brilliantly chronicling who we are and what we as a people have become, is sadly not that difficult to imagine.

Just turn on the evening news.

* * *

EUREKA DAY at Pasadena Playhouse

It’s hard to imagine Jonathan Spector’s hilarious and uncannily newsworthy Tony-winning play Eureka Day, which began in 2018 at the Aurora Theatre Company in Berkeley before playing off-Broadway the following year, wasn’t written in the past few months since our current disastrous and inefficient regime took over our government and started on its mission to kill us all.

The action—if you can call it that as the entire play takes place in one room, the library of a progressive private grade school in Berkeley—revolves around a series of board meetings where the participants discuss the school’s soon controversial policies on vaccinations.

At the play’s start, four of the five executive committee members graciously welcome their new member Carina (Charise Boothe), a position traditionally held by a parent new to the school. There are two anti-vaxxers in the group and as pleasantly as it all begins, soon the attitudes and opinions turn virulent no matter how hard the group’s moderator Don (Rick Holmes), the terminally cheerful head of the school, tries to dodge controversy and temper any raised voices.

All this becomes more urgent when a mumps epidemic sweeps through Eureka Day School and the illness of the daughter of Meiko (Camille Chin), the group’s less unshakable anti-vaxxer, infects and causes a major health issue for the son of fellow committee member Eli (Nate Corddry) during a playdate while their unconventional open-relationshipped parents get it on.

Again, it’s somewhat mind-boggling to realize Spector’s topical dramedy was written and debuted two years before our global pandemic, a time when presumably RFK Jr. was still dumping dead bear cubs in Central Park and his infamous worm was chomping on his obviously now compromised cerebellum.

Things become more and more contentious on Wilson Chin’s cheerful Pee-Wee’s Playhouse meets Sesame Street set as the committee spars and turns from spouting pleasantries (Don finishes each meeting reading a passage from Rumi) to a place where the thin veneer of civilization has been worn away to the bone purdy darn quick.

The major voice of contention comes from the overpowering Suzanne (Mia Barron), who has been part of the committee forever and has had several children enrolled in the school over the years. She is quick to let the newcomer know that her tenure there has made her an important adjudicator in the decision-making process at her beloved school, even to the point of showing her an entire bookshelf of enlightened educational material her family has donated to the library.

Suzanne rules the roost with her delicious scones, frequent interruptions, and syrupy pronouncements that only vaguely hide the fact that if she were any more territorial she would urinate in the corners of the room.

The cast is uniformly excellent, able to completely deliver all the sly nuances and hidden personal agendas slyly tucked into Spector’s sharply insightful script—something that clearly is the real star of the show.

Utilizing a preternatural ability to extricate an amazing amount of acuity about the pros and cons of many opposing contemporary viewpoints on both sides of any issue, Spector never resorts to preaching—simply because his incredibly razor-sharp sense of humor could not possibly be more heightened and obliterates any possibility of anyone having time to take offense.

And his perception does not stop at the clashes between these five people (and eventually an eleventh-hour sixth parent played by Kailyn Leilani). One pivotal and incredibly uproarious scene, when the school has closed down while the dangers of the outbreak are analyzed and the committee hosts an online parent roundtable, provides one of the funniest moments in modern theatre.

As they try to keep the zoom meeting on track, above them the entire thread is displayed on a giant screen. What begins with discussions about whether a missing former board member has moved to Vancouver and other such innocuous pleasantries—each followed by one participant’s continuous use of the thumbs-up emoji to follow almost every post, her online profile photo displaying the face of her cat—soon devolves into far more disruptive dialogue so hostile Don can no longer stay in control.

“This isn’t a fringe opinion!” one parent types. “IT WAS IN THE NEW YORKER!”

Soon people are calling one another Nazis and threatening litigation upon each other until Don simply gives up and shuts down the meeting.

This much talked about scene elicited such a raucous response from the Playhouse opening night audience that the dialogue as the actors try valiantly to interject some proper protocol into the conversation is totally drowned out—something I’m sure could not be more intentional. As many times as Eureka Day has been performed since 2018, I’ll just bet no one has ever heard the dialogue onstage below the onscreen conversation.

Spector’s play is a delightful indictment of the absurdity of modernday manners and wokeness vs. political correctness, but Eureka Day must be a difficult challenge to stage since the actors spend most of the runtime seated in a line across the front of the stage on plastic stackable patio-style chairs. Staging it must be a nearly impossible feat and unfortunately, the contribution of director Teddy Bergman is the production’s only Achilles’ heel.

Unlike what former Steppenwolf artistic director Anna D. Shapiro brought to the Manhattan Theatre Club revival last season that won the Tony Award for Best Revival, Bergman’s staging is static and too often stationary, both in movement and the tools she offers her actors in their effort to bring their characters to life.

Simply, Eureka Day is a brilliant piece of theatre, a play for the ages, and the cast at the Playhouse is worldclass but overall, this mounting of it makes its audience work far too hard to enjoy it despite the non-stop laughs and Jonathan Spector’s unique ability to skewer us all without alienating anyone with a brain not yet done in by an invasive burrowing invertebrate.

* * *

& JULIET at the Ahmanson Theatre / Segerstrom Center for the Arts

What an incredibly entertaining evening in the theatre. I’ve made a few references in reviews lately about big, glitzy Broadway transplants that seem to be geared from the get-go for an eventual run in Vegas at the Mandalay Bay or the Venetian. In the case of the dazzlingly and continually in-your-face national tour of the international hit jukebox musical & Juliet, that’s hardly meant as though that goal is a bad thing.

Produced by and featuring a knockout score highlighting the many familiar pop hits culled from the catalog of Oscar-nominated, two-time Golden Globe and five time Grammy-winning composer Max Martin, as well as a wickedly clever book by the Emmy and Golden Globe-winning and Tony-nominated David West Read, a creator, writer, and executive producer of Schitt’s Creek, you might as well just sit back and enjoy the ride—at least until the rousing curtain calls when the cast quite successfully got the entire audience out of their seats to dance to the music.

Might I mention my nearly 79-year-old ass was up and rocking out right along with the almost every one of the massive Ahmanson Theatre’s energized patrons. Even the most stone-faced opening nighters were moving and swaying, creating a tableaux that must have conjured the image of a gargantuan 1990s-style boy band. I can only hope one of CTG’s roaming opening night photographers got a great shot of all 2,083 of us partying like it was 1999.

This is not saying & Juliet, the imaginative re-envisioning of what happens to Juliet after Romeo dies and she wakes up from Friar Laurence’s sleeping potion and decides she’s not quite ready to join him, is not meant to be anything but what it is: infectious, world-class fun. Slyly, however, after a fairly issue-free first act, there’s more than a little hint of feminine empowerment and equality to satisfy even the most irritatingly left-leaning critics such as Yours Truly.

This is also not saying I wouldn’t always prefer to leave a theatre gloomily contemplating the death of Willie Loman’s American dream, or sad that poor Blanche had to rely on the kindness of strangers, or wondering if that broken Shelley “The Machine” Levene would die in prison. That’s just overdramatic, melancholy me.

I personally would rather musicals that take on powerful contemporary issues facing us all, like Next to Normal or Fun Home or Sondheim’s Passion, but getting any kind of brief respite from the reality of watching everything to believe in crumble around us at the hand of a mad authoritarian and his somnambulant supporters, is right now a consummation devotedly to be wish’d.

There’s no doubt this production—which began in Manchester, England in 2019 before moving on to winning three Oliviers in the West End and nine Tony nominations, including Best Musical, on Broadway in 2023–is a big’un. The glorious & Juliet is surely one of the grandest of the grand visually, with its snappy, deliciously tongue-in-cheek book by Read, chockfull of crafty Shakespearean references and puns upon the original puns, all perfectly complimented by massive, eye-popping sets by Soutra Gilmour, Andrzei Goulding’s elaborate video projections, Howard Hudson’s lighting, and especially the colorfully updated pseudo-Elizabethan costuming by Tony-winner Paloma Young.

Luke Sheppard’s direction keeps things moving at a breakneck pace, but the spirited hip-hop-inspired choreography by Jennifer Weber, eagerly performed with expert precision by this outstanding company, is one of the production’s greatest assets. It’s a joy to see this ensemble of masterful contemporary terpsichoreans, who… well… let’s just say don’t all fit the standard image of what constitutes a Broadway dancer, allowed to show the world they are perfectly capable moving as vigorously and powerfully as their less zoftig castmates. As someone whose physicality greatly hampered my own career over the years, it’s a personal thrill for me to see real people trusted to strut their stuff no matter how much stuff they have to strut.

Of course, the entire production revolves around 25 years of the multi-award-winning chart topping pop songs of Martin, the Swedish composer/producer named ASCAP’s Songwriter of the Year a whopping 11 times. The audience, many of whom are obviously rabid millennial fans of the prolific songwriter, often start applauding and whooping during a song’s first few downbeats, then go wild when they realize how handily Martin and Read have managed to incorporate the familiar tunes into vehicles for the show’s leading characters.

Considering Martin’s collaboration with some of the most heavyweight musical stars of the past quarter-century, including Britney Spears, the Backstreet Boys, Ariana Grande, Katy Perry, N*SYNC, The Weeknd, Demi Lovato, Pink, and many, many more, the program credit is listed as “Max Martin and Friends.” Some of the most famous tunes included in the whooping 32-song cycle are “I Want It That Way,” “Baby One More Time,” “Oops! I Did It Again,” “Since U Been Gone,” “I Kissed a Girl,” “Roar,” “Larger Than Life,” “Blow,” “Fuckin’ Perfect,” “That’s the Way It Is,” and “Can’t Stop the Feeling.” You get it: epic. No wonder they’ve called the uber-prolific Martin the Shakespeare of Pop Music long before & Juliet was a twinkle in his eye. Ironic, isn’t it?

On top of all the other high points of this production, there is the cast, featuring some of the best vocal talent assembled in one place in a long time. In the title role behind the &, Rachel Simone Webb commands a true star-making turn as the all-new and nicely “woke” Juliet, a quite feisty young maiden who is suddenly unwilling to let others, from her soon reanimated husband of four days to her controlling parents, make life decisions for her. And as a singer with lung power to rival Byonce, Webb could one day soon become a major star right up there with some of the artists who originated the songs she belts right out into the Music Center Plaza.

Cory Mach has a field day as the stuffy Shakespeare, around dealing with his long-suffering wife Anne Hathaway (Teal Wicks), who early on arrives on the scene to demand her husband rewrite the ending of his famous play with her input. Wicks is wonderful as Anne, bringing a kind of all-elbows Sutton Foster-y presence to the wife also intent on finding her own voice.

Mateus Leite Cardoso is a delight as Francois, the painfully introverted nobleman who becomes Juliet’s new intended, as is Nick Drake as Juliet’s bestie who soon shows her reluctant fiancé what his true nature really is. Drake stops the show assigned to deliver the unlikely ballad “I’m Not a Girl, Not Yet a Woman,” a task he quickly makes all his own. Kathryn Allison is also noteworthy as Juliet’s faithful nurse, especially in her scenes falling in love—on her own terms as well—with Francois’ Bluto-esque yet eventually softhearted bass-baritone father Lance (Paul-Jordan Jansen).

Ben Jackson Walker, Broadway’s original back-from-the-dead protagonist whose name has been removed from the musical’s title, gratefully returns to the role during the show’s LA run. Walker was born to play this Romeo, a rascal cocksmith who, before finding his true love, had trouble keeping his codpiece in his tights. By the end, however, overwhelmed by the strength and maturity his love has managed to adopt, his Romeo becomes a whole new person desperate to win her back. It’s not often a frothy musical features a character with such a drastic arc to navigate and it’s hard to imagine anyone nailing it more effortlessly than Walker.

The rest of the ensemble couldn’t be better, especially in their ability to keep things moving at fever pitch at all points.

I have to say I couldn’t have enjoyed & Juliet and what has gone into it to make it so spectacular on every level more, but I do think over time, unlike other musicals I’ve found as impressive, this one might not stay in my addled brain as indelibly as others. It’s kinda like that old adage about Chinese food, that it could not be more delicious or tasty but an hour later you’ll be hungry again.

I can live with that and, I suspect, the creators and the producers of & Juliet will be able to as well. Howsoever it eventually lingers in my overworked memory banks, respect for everyone involved and for unique commitment to get a couple of thousand old duffers out of their seats and jammin’ to Max Martin’s “Can’t Stop the Feeling” by the show’s end, is an accomplishment not even Rodgers and Hammerstein or Sir Stephen ever made happen.

* * *

JUST ANOTHER DAY at the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble

On designer Pete Hickok’s basically bare stage evoking a serene city park, two elders (Patty McCormack and the playwright Dan Lauria) meet every day in Lauria’s sweet, gentle two-hander Just Another Day, now making its Los Angeles debut at the Odyssey after successful runs off-Broadway and at Trinity College in Dublin.

The play quickly evokes a contemporary senior citizen version of Beckett’s classic Waiting for Godot as the sprightly twosome, on a continuous loop of banter of various degrees in importance, are interrupted by an off-stage “woman in white” who rings a bell when they get too agitated—or too frisky.

They repeatedly try to remember when and how they have known each other and soon the faux-absurdist little dramedy makes it clear—well, relatively clear—they are Alzheimer’s patients in the garden of a facility where they are living out their lives. They may have once been comedy writers who worked as a team, they may be a long-married couple, she may have been a poet, he may have been a stand-up comedian.

Under the sharply tuned direction of New York educator and theatre producer extraordinaire Eric Krebs (once artistic director here of Geffen Playhouse in a too quick residency on our coast), Lauria’s script is often clever and extremely well written. It is occasionally bittersweet, often quite funny, and at times quite poetic.

The pair, who reflect that they are an “anachronism and no longer needed,” often find they link the most when discussing classic films and the great movie iconic stars of the silver screen, many of whom flash by in massive (uncredited) old Hurrell-style photos on the stage’s back wall.

At one point, Lauria’s character (the roles are only called Man and Woman) brings up the Three Stooges and she wonders how many people in the audience will still even know who they were.

“Shame on them if they don’t,” the Man bellows in response and my first thought was it was lucky Just Another Day debuted at the Odyssey, where the usual average age of most patrons in the audience is about 285–and that includes me. Except for one kid about 16 we saw return to his seat at intermission, my theatre-date friend Rachel Sorsa had to be the only other audience member in attendance at this Sunday matinee not on Metamucil.

There have been many plays, books, films, and even documentaries dealing with Alzheimer's and aging in general. I am personally quite attuned to such material, as I deal with caring for someone with whom I’ve lived for 56 years as he slowly, painfully disappears right before my eyes on a daily basis.

Because of this, I suspect I have a bit of an Achilles’ heel hampering my total objectivity when confronted with memory loss as a subject, which is why, especially because Lauria's writing is slick and accessible and the performances by two such noteworthy seasoned performers are golden, I was dismayed to find myself not at all moved or emotionally engaged in the play.

Still, to see actors such as Lauria (best known as the patient father on The Wonder Years) and McCormack (Oscar nominee at age 9 as the evil Rhoda Penmark in The Bad Seed) bounce off one another’s talents live onstage is a treat and there are plenty of moments to make your attendance worthwhile.

As much as I left the theatre feeling the classily produced Just Another Day never quite connected with me personally, the exploration of one major theme will stay with me for a long time to come:

“As long as we create,” the Man tells his feisty sparing partner, “we are not lost.”

* * *

REEL TO REEL from Rogue Machine in collaboration with HorseChart Theatre

What the heck, Rogue Machine? I keep worrying with each new opening that this will be the one. The dog. The misstep. How can you guys keep churning out amazing productions one right after another?

In the LA premiere of John Kolvenbach’s Reel to Reel, co-produced by the Machine in a second collaboration with the HorseChart Theatre Company, the 55-year relationship of a quirky yet somewhat oddly undistinquished Manhattan couple is explored while traveling down a remarkable non-linear path, morphing seamlessly from scene to scene, slipping back and forth in time from the early clash of forging a comfortable togetherness to the lovers’ cranky but still devoted finale dealing with those so-called golden years.

Maggie is a driven cult-centric performance artist who creates her art using sound effects featuring those ordinary clicks and drips that define our everyday lives, all punctuated by secretly purloined snippets of conversation, while her husband Walter is an unsuccessful filmmaker who begrudgingly lives in the shadow of his wife’s unstoppable creative energy.

Not that he doesn’t have his own mission in life in its latterday stages: “I’m trying to outlive my vanity,” he offers. “That’s my project.”

We become privy to the couple’s many idiosyncrasies developed together—or more accurately patiently and lovingly overlooked—over the course of five-and-a-half decades as Kolvenbach’s incredibly neck-jerking script swings rapidly through time with near-manic spiritedness.

With all the demands inherent in how any couple changes and shifts and settles in during a long-term marriage, the roles of Maggie and Walter are played by a quartet of remarkable actors whose work together could inspire a master class in ensemble performance. Venerable veterans Alley Mills and Jim Ortlieb star as Maggie and Walter at age 82, while their younger counterparts at ages 27 and 42 are assayed by Samantha Klein and Brett Aune.

Everything about Reel to Reel is downright extraordinary in a rather unextraordinary way, especially in chronicling a wildly covetable love between two people even when each complains about the other’s kinks and eccentricities. “Whatever you may see,” Walter prophetically observes, “it’s all mostly your own reflection.” If that isn’t a perfect description of surviving any relationship, I don’t know what is.

What Kolvenbach has created could so easily slip into gimmickry but never does it stop being fascinating, even in its enveloping ordinariness. The playwright’s power to weave through time with ease, bringing insight and understanding to the couple’s complicated relationship while resisting the temptation to push his characters into even a single tragic situation—besides one typically unhinged and, in retrospect, nonsensical argument—makes this one of the best and most moving plays of the year.

Through the decades, their story is continuously punctuated by sound, from Maggie’s many recordings of simple private whispered conversations to all the noises of life which anyone would find familiar. Magically, those sounds are delivered by the actors themselves, executing sound designer Jeff Gardner’s remarkable foley plot in clear sight behind the movable gossamer scrims of Evan A. Bartoletti’s highly flexible set evoking a series of Japanese paper screens.

Now, I needed to ask for a copy of Kolvenbach’s play to read before I could comment on what exactly director Matthew McCray’s continuously fluid staging contributed to the production. Indeed, I discovered most of the innovation was provided by McCray’s signature visionary imagination; in the script, the foley is suggested to be performed in chairs placed on either side of the stage rather than as something smoothly assimilated into the action. McCray’s complete understanding of the dreamlike aspects of Kolvenbach’s tale becomes like another character, as does Gardner’s omnipresent foley design.

The precision quartet of actors are forced not only to find a path to make their complex characters and their riveting love for each other real and honest, but at the same time they must meld their flashes of often interrupted dialogue into poetry as though playing the final scene in Michael Cristofer’s The Shadow Box—all the while doubling as stagehands, generating the breakneck foley and the play’s meticulously choreographed scene changes. I can only bet rehearsing for opening night must have been something of a marathon experience and in a perfect world, these folks will surely be a shoo-in for Ensemble Cast of the Year honors.

There’s a lingering message in Reel to Reel that made my partner and me squeeze our hands together even tighter than usual in the darkened Matrix, something I'll take away with me like a badge of honor and will surely never forget. “The less we do,” Walter shares with his lifelong love, “the more at home it feels.” I have no idea what age John Kolvenbach might be but if he isn’t as long-in-tooth as I am, he certainly has an uncanny ability to channel the simple wonderments of life as though he’s lived 'em many times before.

And listen here, Rogue Machine, cuzz’n I’ve got sumptin’ important to say:

Your current season deserves one of those special regional Tony Awards this spring like the one Pasadena Playhouse was given last year. You’ve proven yourself to be a company to admire over the last few years but truly, what you’ve accomplished and shared with our grateful community in 2024-25 alone has been something almost miraculous.

* * *

A BEAUTIFUL NOISE at the Pantages Theatre / Segerstrom Center for the Performing Arts

It’s a given that most theatre critics are consistently sour on what has become known as “jukebox” musicals—huge, grandly glitzy, even possibly intentionally sterile productions mounted with cashcow commercial success and a future open run in Vegas as the main goal.

I have become far less fault-finding about such presentations, particularly because they thrill audiences and bring the butts of a lot of people who wouldn’t usually attend live theatre into the seats. Besides, I have a special affection for the blatant overindulgence of Vegas, a place where I once spent a lot of time when writing a monthly column about entertainment in Sin City for a national magazine.

Without much deeper thought, I expected the national tour of A Beautiful Noise, now playing at the Pantages, to fall into that category and simply be a traditional “And-Then-I-Wrote” musical featuring the songs and exploring the life story of Neil Diamond. I was resigned to that, especially since reviews in New York were generally mixed.

Indeed, there’s no doubt the Noise-y production numbers could not be more flashy and resplendent—especially as staged by choreographer Stephen Hoggett, creator of the movement in the last tenant of this same theatre, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, so good it nearly overshadowed the show’s jaw-dropping special effects.

I basically loved just about every aspect combined to create A Beautiful Noise, which almost instantly transcends the dreaded jukebox distinction. Anthony McCarten’s book for the musical begins quietly with Diamond in his retirement years (Robert Westenberg), alone onstage uncomfortably seated opposite a psychotherapist (Lisa Renee Pitts, so memorable in The Father at Pasadena Playhouse a few seasons back) and wishing he could be anywhere else on earth. The infamously insular superstar is there not by his own choice but instead is sitting through what he sees as an agonizing invasion of his privacy at the insistence of his wife Katie.

When the doctor hesitantly mentions the constant companionship of Diamond’s woe-is-me dark cloud of a demeanor, he quickly snaps back, “But what if woe is me?”

As the patient shrink tries valiantly to keep him from bolting, she finds a perfect tool to get the guy to open up: a secondhand copy of a book called The Complete Lyrics of Neil Diamond. As she opens the massive coffee-table-sized tome and starts reading off some of the poetry that, along with a voice once described as “gravel wrapped in velvet,” helped make him a legend, this new intrusion into his fiercely guarded psyche is definitely not something that makes her victim any more comfortable about having his head shrunk. Still, as it all unfolds, the world of the songwriter’s 60-year career begins to come alive all around them. Literally.

To say Diamond’s incredibly prolific body of work takes on a life of its own would be a drastic understatement. Suddenly the stage opens up with 20-something extremely talented triple-threat performers inexplicably popping out from the back of Diamond’s leather chair and, looming behind them, a dynamic 10-piece band appears—all joined together to explore the music and life of one of our time’s most successful and historically melancholy musicmakers.

The scene work recalling pivotal moments in Diamond’s life rises above the usual musical theatre romanticized fluff versions of actual events; nothing is glamorized in telling the story of a man who, besides fame, fortune, and the admiration of millions, never was able to shake off a lonely childhood and a lifelong struggle with depression and self-worth.

In the musical numbers, however, none of the razor-dazzle of Broadway is overlooked or underutilized. David Rockwell’s uber-flashy neon-infused sets, Kevin Adams’ extraordinarily dramatic lighting, and particularly the seat-shaking sound design of Jessica Paz, fills the Pantages as never before—not an easy task considering the majestic one-time movie house’s longtime acoustical challenges.

Under the smooth and imaginative direction of celebrated Tony-winning director Michael Mayer, A Beautiful Noise might have been mounted with profits as a motive for its creation, but that’s nowhere near what it accomplishes.

Perhaps inspired by the equally raw and revealing Jersey Boys before it, the conflicted private life of an icon who has sold some 130 million albums worldwide—surpassing even Elvis—is not glossed over in any way and becomes the surprisingly compelling takeaway from this production.

In the demanding role of the younger Diamond, Nick Fradiani offers a marathon performance. Hardly ever leaving the stage except for frequent costume and wig changes, he plays the singer/songwriter from his hermetically sealed teen years through his early days trying to hawk his wares around Tin Pan Alley, then on through an early “ownership” by the Mob, three marriages, and the breakneck pace of an incomparable career touring the world with a compulsion to escape unhappiness by never stopping.

Fradiani, the 2015 American Idol winner, proves himself to not only be a phenomenal performer, but if you close your eyes and just listen to him sing, you’d swear Diamond himself was calling in the vocals from his home near Aspen—which he actually did for the Pantages’ opening night, by the way, joining in for a rousing finale of the classic “Sweet Caroline.”

You know: Bum-Bum-BAH and all that.

Both Hannah Jewel Kohn and Tiffany Tatreau have memorable moments and breakout solos playing his long-suffering former wives, while Kate A. Mulligan as a crusty Brill Building music producer with a heart of gold steals the show at her every turn.

Although at first Westerberg seemed a tad one-note as the older Diamond, his performance delicately blossoms and enrichens as the story unfolds and his character begins to find a well-deserved sense of peace.

Interestingly, it’s not often that the most compelling thing about a musical production is the work of the ensemble but here, the 10 sensational young artists who make up what the program calls “The Beautiful Noise” become the heart of the production.

Usually a musical’s chorus/dancing ensemble is made up of long-legged, physically uniform Barbie and Ken clones, but not here. As though assembled by Susan Stroman, these folks aren’t your standard gypsy “types” by any means, but they all move and sing and act without missing a beat.

The band, led by keyboardist James Olmstead, is also a tremendous asset, with a huge shoutout to Morgan Parker for some mighty impressive drumming.

No matter how entertaining or lavishly produced a musical may be, it’s not often in my life I can say one of them changed my perspective as clearly as this. I must admit, although some people who know my music business background during the golden age of rock might find it surprising, an appreciation for Neil Diamond was never on the top of my list.

Although for me personally Neil was always a sweet and humble guy to run into during the days when the biggest celebrities on the planet frequented our Troubadour “front bar” as a place where they could hang out unbothered by fans and paparazzi, my tastes always were more about Joplin wailing the blues and an infinity for the Birkenstock-sandaled Lookout Mountain crowd.

My problem was always his delivery, the sequins and fringe and a penchant to stage a show that rivaled the over-produced pizzazz of Liberace.

I certainly enjoyed the precisionally-produced musical excess and fine performances delivered in A Beautiful Noise, but what I will remember most dearly is how it changed my perception of the artist it honors. Thanks to the unexpected depth of Anthony McCarten’s script, the infectious catchiness of Neil Diamond’s music and the genius of his lyrics suddenly superseded the hype and made me understand for the first time that this guy, with his sparkly over-the-top Evel Kneviel wardrobe and extravagant production values, was desperately trying to hide the lonely, broken kid from Brooklyn still crying out from inside.

* * *

YANKEE DAWG YOU DIE at East West Players

Philip Kan Gotanda’s now classic two-hander Yankee Dawg You Die begins with a chance meeting at a glitzy Hollywood party in 1988 between an overconfident young Asian-American actor on the rise, whose main credit at this point is overshadowed by the rumor that he was almost fired from a play in New York, and an established veteran whose long and successful film career, as what he refers to as an “oriental” performer, has spanned many years and includes an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor.

The main conflict for the ages is typically generational. Bradley Yamashita (Daniel J. Kim) at first gushes to Vincent Chang (Kelvin Han Yee) about being a longtime avid fan of his work but the more he opens his mouth, the more his proverbial foot gets stuck in it. For Vincent, his career has been playing countless stereotypical Asian roles in low budget movies—a term that Bradley quickly corrects, instead saying that the more contemporary description of the older icon’s career is that he's been working in independent films.

What starts off as an excited outpouring of the newbie’s respect for his elder rapidly turns sour, especially when he mentions one of Vincent’s more recent performances in a movie about Tokyo being attacked by a giant salamander, featuring the actor appearing with overgrown hairy facial appliances, made him “look like a fucking chimpanzee.”

The ongoing clash between these two perspectives is quickly evident. Vincent is proud he’s worked steadily in film for years and has never turned down a part offered him. Bradley sees it differently, later referring to his predecessor as someone who spent his life acting like a Chinese Stepin Fetchit.

Indeed, despite his Oscar nomination, most of Vincent’s roles through the years had been playing Vietnamese prison commandants, genuflecting waiters, and other standardized Asian characters, all roles he played willingly while riding along on the wave of what much earlier in vaudeville was derogatorily dubbed the Chop Suey Circuit.

Gotanda’s groundbreaking Yankee Dawg, now in an electrically charged revival at East West Players chosen to honor the company’s prestigious 60th anniversary year, was first performed at Berkeley Rep in 1988 before being brought to Los Angeles Theatre Center later that year and journeying on to a much-acclaimed run off-Broadway at Playwrights Horizons in 1989.

It was first revived at East West Players in 2001 and the fact that all these years later it is still an important seminal work in the canon of Asian American theatre makes it the perfect choice to mount again nearly a quarter-century later. The conflicts that develop between the brash hopeful, who believes with all of his naivete that he can break barriers and redefine how Asians are represented onscreen, and the world-weary acceptance of his older counterpart who has spent his entire career forced to assimilate into the narrow-minded demands of Hollywood in its heyday, is still a fascinating journey.

Along the way, what initially develops into a prickly adversarial relationship evolves into a bond that changes the life and worldview of each of these two men. Under the visionary direction of Jennifer Chang, who inventively modernizes the production by incorporating live and recorded video projections into this retelling of Gotanda’s cautionary tale, it could not be more pertinent today.

Keeping in mind that much has changed in our industry and Asian actors have today indeed been afforded far more respect and appreciation in our insular universe of arts creation, the world around us still has a long way to go to catch up.

Kim makes an auspicious EWP debut as Bradley, able to find both the character’s early cockiness and, through the production’s intermissionless 90 minutes, successfully morphs into a more accepting guy who finds an all-new respect for someone who might not be that different from him after all.

Still, it is Yee who makes the most solid and indelible impression as Vincent Chang, especially when he stops being respectfully polite and makes sure this upstart knows he wouldn’t be anywhere near where he is in his career if it wasn’t for all the crap that he and his generation silently endured just to survive in the hardhearted and brutal business called show.

Added to the many wonders of this magical and important return of Yankee Dawg and Gotanda’s insightful exploration of Asian American identity and early representation in the entertainment industry is the fact that Yee originally played the younger character in that very first production at Berkeley Rep nearly 40 years ago. How I wish I could jump into my handydandy time machine and return to see that production in which he starred opposite iconic actor Sab Shimono who, luckily for opening night audiences at EWP last Sunday, made a surprise appearance and joined the actors, director, and playwright onstage for a prolonged and enthusiastic standing ovation.

We must remember as our country and all we hold dear crashes and burns around us at this terrifying crossroads in the course of human history that it is art that slowly and gradually heals the world. Philip Kan Gotanda’s exceptional wordsmithery helped change the perception and acceptance of Asian actors over the course of the last 37 years—and obviously continues to do so. Much has been accomplished since Yankee Dawg You Die first debuted, yet indisputably we can't stop speaking out now more than ever before.

* * *

THE RESERVOUR at Geffen Playhouse

A new play about struggling with addiction, dealing with cognitively aging grandparents, and winning back a parent who’s given up on you. Sounds like a laugh a minute, doesn’t it? Well, surprisingly, it is.

The world premiere of The Reservoir at the Geffen heralds the auspicious professional playwrighting debut of Jake Brasch, someone with a unique ability to reveal more autobiographical shit about himself than even Jonathan Safran Foer could call forth—and who with this play instantly emerges as a major dramatist with a career to watch as it rockets to the heights.

On Takeshi Taka’s minimalist abstract set possibly meant to conjure a CT-scan slide of Brasch’s brain, The Reservoir begins as the writer’s alter-ego Josh (Jake Horowitz in a phenomenal, marathon performance) wakes up on the shore of a Denver reservoir with coughed-up schmutz caked on down the front of his Cosby sweater and little idea how he got there.

Having taken a medical leave from NYU, where’s he’s been a theatre major considering writing a queer-themed 12-step-oriented musical called Rock Bottom, it seems Josh instinctively headed home to Colorado to see if he could once again get sober with the help of his family. His long-suffering mother (Marin Hinkle) has been through this process many times before with her chronically alcoholic mess of a son, however, and isn’t exactly anxious to open her arms for another dose of heartache.

Josh turns to his grandparents for solace and acceptance, but in doing so realizes both sets of his eclectic elders are overwhelmed by problems of their own.

All four of his once-sharply focused grandparents are in the midst of some degree of cognitive decline and Josh, in an effort to save himself through becoming a champion determined to help slow their symptoms, discovers the concept of Cognitive Reserve, a theory that by keeping the mind and body challenged, the descent into dementia and Alzheimer’s can be diminished.

Of course, this is an admirable mission, but is it more about distracting himself to keep him from drinking vanilla extract by the bottle than it is saving them?

It’s obvious and hardly a secret that Brasch is writing about his own recovery and his own struggles with sobriety and finding his way through questions regarding his sexuality, his sense of worth, and trying to unravel how his Jewish roots figure into his battle against those incessant demons.

Creating this amazing work of incredibly personal art is a gift for us all—and the fact that Brasch can accomplish bringing us along on his difficult quest with such a welcomingly twisted sense of humor is revelatory.

His maternal grandmother Irene (Carolyn Mignini) is the worst off, relegated to a care facility and, although no longer really capable of holding a conversation or even acknowledging Josh’s presence, she can sing a few verses of unseasonal Crissmiss carols like a retired member of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.

Her husband Hank (Geoffrey Wade), although still With Us, seems totally unaware of his descendant’s all-too public struggles when he runs into him at a bookstore while looking for a copy of The Fountainhead to give to his gastroenterologist, while his paternal granddad Shrimpy (Lee Wilkof) is not only enlightened but more than willing to make some knee-slapping jokes about Josh’s drinking or his sexuality.

Still, Josh’s strongest bond is with Shrimpy’s ex Beverly (Liz Larsen), a feisty no-nonsense electrical engineer who helps her grandson more than any of the others—even though she professes outright that she would prefer not to have to be so close and nurturing with him.

Director Shelley Butler is the quintessential partner for the unstoppable imagination and quirky style of Brasch, collaborating with him to implement his balls-out narrative devises, including moments when light changes signal that Josh has left the scene and is instead talking directly to us—prompting after one such episode for Beverly to ask him, “Where do you go when you do that?”

In fact, both pairs of grandparents stay seated upstage through most of the action, ready to step into the story at a moment’s notice and willing to comment on what’s happening even if they’re not really there. It’s a fascinating and wildly inventive example of the lack of limits inherent in creating theatrical magic.

Along the way, as Josh desperately attempts to heal, Brasch finds moments to mine humor in unexpected ways, sending up everything from vegan anarchist co-ops to senior aerobics (with Hinkle doubling as an ‘80s-esque Jane Fonda-like exercise guru who introduces herself as “I’m Jeanette and I’m a visionary”), and on to Shrimpy’s admission that he’s 85% straight but likes to look at images of dicks on his computer.

To say Butler’s cast is golden is a huge understatement. Horowitz is absolutely stunning as Josh, one of those roles that could make any actor sleep 18 hours a day between performances to keep from crashing.

All four actors playing his goofy grandparents are superlative, especially Wilkof’s charmingly off-kilter Shrimpy (no one’s called him Milton since grade school), who refers to his recently diagnosed condition as “diet Alzheimer’s,” and Larsen, who gives a standout tour-de-force performance as the tough but loving Beverly.

Hinkle is almost unrecognizable as she zips between supporting characters, as is Adrian Gonzalez playing a series of characters, including a beach cop, an abrasive psychologist author, and especially as Josh’s patient manager at a local bookstore who's hiding some heady secrets of his own.

This troupe of veteran performers are the heart of The Reservoir, which would never work as well without such talent and a palpable willingness to believe in Brasch’s outrageous over-the-top characters.

Still, it’s all about the discovery of a brilliant new dramatist whose star, with this exceptional debut, has clearly been launched into the stratosphere and I suspect will soon be recognized as one of the brightest in the galaxy.

As it was with early Durang or Charles Mee, some people might be a tad put off by Jake Brasch’s idiosyncrasies, his intrepid honestly, and his willingness to bare his soul, not to mention his delightfully skewed and inappropriate playfulness dealing with some usually dead serious subjects.

Personally, as a longtime primary caregiver to a partner slowly disappearing into dementia and Alzheimer’s, I was more than ready for a good swift kick in my poor-me pants provided by his bold and dark sense of humor.

“How many Alzheimer’s patients does it take to screw in a lightbulb?,” Shrimpy asks.

“To get to the other side.”

* * *

PARADE at the Ahmanson Theatre

As someone who’s been active in theatre as an actor, director, playwright, and teacher for over seven decades and has been writing reviews of live performance for close to 40 of those years, all despite the uphill journey of championing such things tirelessly in a world more interested in real housewives and eager to know if TayTay and her… er… Tight End are still together, there are times when it begins to feel as though it’s been a waste of time.

I guess burnout is an issue in every profession but for me, when it hits, it hits bigtime, and I begin to wonder if my quest for windmills has been taken over by a geriatric lack of wind.

Then suddenly something comes along such as the six-time Tony nominated revival of Alfred Uhry and Jason Robert Brown’s 1998 musical Parade, which won the authors Tonys for Best Book and Best Score, respectively, when it was first presented and this time out won for Best Revival of a Musical in 2023 and received incredibly deserving Best Director honors for Michael Arden’s visionary reinvention.

Now energizing the Ahmanson with both its expansive reconceptualization and its uncanny timeliness in calling out injustice and inequality as our own city finds itself under siege by a whole new breed of racists and powermongers, this Parade is far more powerful than squeaky military tanks and embarrassed-looking foot soldiers (once referred to as “suckers” and losers” by the Velveeta Voldemort) could ever conjure.

Uhry’s controversial subject matter for Parade has little in common with musicals about unseemly ogres arriving to rescue feisty princesses or dipshit teenyboppers proving Harvard Law can be an adorable place to study. It is truly the quintessential definition of what constitutes—and what bravely attempts to push the boundaries of—the genre of musical theatre.

Probably the last thing most artists would tackle when deciding to morph real life events into a musical would be the story of Leo Frank, a Jewish factory supervisor living in Atlanta who, in 1913, was glaringly railroaded and convicted, primarily because of his ethnicity, for the murder of one of his 13-year-old female employees.

It’s an ominous and ugly tale of prejudice, corruption, and broken dreams, yet somehow Pulitzer/Oscar/three-time Tony-winning playwright Uhry, along with lategreat Broadway superstar producer/director Harold Prince, believed the tragic saga of Frank and his loyal wife Lucille was worthy of a musical treatment.

Thanks to their sense of innovation and the richly semi-classical score by Brown, Parade is more a dark and brooding opera than it is a musical entertainment, something made gloriously noteworthy by Uhry’s absorbing account of one of the most barbaric moments in our country’s troubled history.

Brown’s contribution is the icing on the cake, giving a surprising number of performers in the 33-member ensemble their own individual chance to shine—and shine they do.

Perhaps one of the most exciting aspects of this particular mounting of the epic production is the cast. Under the exceptional musical direction of Charlie Alterman, this may be the most gifted group of vocalists gathered together on one stage I’ve been swept away by since 1985 when Porgy and Bess was indelibly revived by the Metropolitan Opera.

In the demanding role of Leo Frank, Max Chernin gives a dynamic, many-faceted performance that also quickly rises above the traditional limitations of musical theatre, growing and maturing and becoming ever more courageous as the character faces the inevitability of his fate.

As his stalwart wife Lucille, Talia Suskauer also finds a clear arc as the unstoppable spirit of her character’s evolution from dutifully subservient spouse to fiery, assertive advocate for her husband’s vindication becomes a clear path that would be easy to find a tad implausible.

Together, Chernin and Suskauer manifest a love and devotion between two people that is nothing short of awesome, something solidified by their emotional duets, “This is Not Over Yet” and the hauntingly beautiful eleventh-hour ballad “All the Wasted Time.”

As I mentioned, Brown has given almost all of the supporting players their own individual spotlight in his stirring song cycle, from Chris Shyer as standup Governor John Slaton (the mood-lifting “Pretty Music”) to Jenny Hickman as the grieving mother of the teenage victim (“My Child Will Forgive Me”) to Andrew Samonsky and Griffin Binnicker as the Trump-like villainous prosecutor and future Governor Hugh Dorsey and his pretend-pious ally Tom Watson (“Somethin’ Ain’t Right” and “Hammer of Justice,” respectively).

As the threatened witnesses coached to lie on the stand by Dorsey, Danielle Lee Greaves as the Frank’s compromised housekeeper (“Minnie’s Testimony”), and Robert Knight and Ramone Nelson as two factory workers led astray (“I Am Trying to Remember” and “That’s What He Said”), are all unforgettable in their own right.

In the musical’s prologue, “The Old Red Hills of Home,” Trevor James and Evan Harrington perfectly set the mood for the then-still rural Atlanta community fiercely proud to fight for their country, while perhaps the most infectious supporting performance comes from Jack Roden in an auspicious professional theatre debut as Frankie Epps, the dear, sweet young kid swept into the fervor of war, displaced values, and the enveloping shroud of racism and national pride. His rendition of “It Don’t Make Sense” is a heartbreaker.

Casting director Craig Burns and the Telsey Office deserve exorbitant praise for assembling this incredible, uniformly inspirational troupe of actors with voices beyond the best—but of course, the catalyst for what makes them so able to be incandescent is the gorgeous, heroic score by Jason Robert Brown, heir to the mantle as one of the greatest musical theatre composers of all time, each magical link of its chain forged through the years by the likes of George Gershwin, Kurt Weill, and Brown’s obvious mentor Stephen Sondheim.

Aside from the genius of Brown and the once again current urgency of Uhry’s message about intolerance and cultural confiscation in pursuit of ruthless political ambition, what lifts this revival into the stratosphere is the Tony-winning vision of director Michael Arden, who breathes a whole new passionate, highly kinetic life into an originally quite austere production that even the legendary Harold Prince himself failed to deliver with any palpable ardor.

Along with the choreographic team of Lauren Yalango-Grant and Christopher Cree Grant, most of the large ensemble seldom leave the stage, often when not in the action staying seated as observers on either side of set designer Diane Laffrey’s political platform of a playing space adorned with patriotic stars-and-stripes banners.

The continuous three-ring circus of movement is grand in scope and could have proven to be a boldly precarious choice but instead, it makes this production radiate with one of the best uses of design elements and performance showcasing in the history of modern stagecraft.

Any thoughts I may have had bubbling up lately about the ineffectual nature of the championship of great art—especially as the American theatre still fights with all its might to crawl back into relevance since the end of the pandemic—have been sent packing. The excitement this thrilling new materialization of the overlooked wonder of Parade, and the sheer brilliance and importance of what Alfred Uhry and Jason Robert Brown gifted the world 27 years ago, has renewed my sense of purpose in a fresh and exhilarating way.

* * *

HAMLET at the Mark Taper Forum

All I can say is they I must have better drugs than the rest of my colleagues. Playwright/director Robert O’Hara’s irreverent adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, commissioned and developed right here by the Center Theatre Group and now world premiering at the Taper, has been almost unanimously eviscerated by my fellow members of the LA press community—and I cannot possibly disagree more.

“This is a fucked-up place right here,” a character comments about the proceedings early on, an observation I personally found tremendously promising.

If there’s anything about this production I might have qualms about, it’s the title. If there are any potential patrons out there who aren't familiar with the work of O’Hara, they might think they’re about to see a traditional mounting of one of our most familiar classics, not realizing they’re about to see the title character going down on his Ophelia at first lights-up or watch him push the face of his on-the-side boytoy Horatio into his crotch, giving a whole new meaning to asking his bestie to “Swear on my sword” and “Play on my pipe.”

Later, in a conversation with Ophelia during the time when their mutual love interest has been shipped off to England, he tells her Hamlet has sent him letters too—and in iambic pentameter.

“Oh yeah,” she agrees, “that’s kinda his thing.”

I’ve heard a couple of remarks that ol’ Will must be spinning in his 409-year-old grave thanks to O’Hara’s assault on tradition, but I suspect it would be the contrary; I’m not entirely sure that the often bawdy and sly ol’ Bard didn’t have this exact same thing in mind way back in 1599. I’ll bet he’d applaud this bold and unhallowed interpretation but then, as old as I am, despite rumors suggesting otherwise I actually never met the guy.

Still, maybe it would have been better if O’Hara’s revision had been titled Hamlet Redux or Hamlet Deconstructed so everyone interested would instantly know they weren’t seeing a stripped-down version told in two hours without an intermission and that the production’s last third turns out to be an all-new and rather comedic riff on the original.

While the first two-thirds of O’Hara’s Inappropriate Night’s Dream remains a CliffNotes version of the tale, the final third morphs into an investigation of the pile of bodies stacked up by final curtain. Led by one trenchcoat-clad Inspector Fortinbras (played by Joe Crest, who also impressively doubles as the Oz-like projected head of Hamlet’s Ghost), this unexpected reinvention suddenly transforms into a clever tongue-in-cheek crossover between Columbo and The Pink Panther.

The story is filtered through what we see as a darkly atmospheric old film noir produced by something called the Elsinore Picture Corporation, a device further conjured by the production’s incredible design aspects. Clint Ramos’ grandly sweeping yet classically austere set design becomes the quintessential blank canvas for Yee Eun Nam’s moody and often jarring (and certainly potentially award-winning) projections, Lap Chi Chu’s starkly spectral lighting, and Lindsay Jones’ often unearthly sound and original music.

As Hamlet, someone another character observes “thinks he is in a Shakespeare play,” Patrick Ball (an actor unknown to me but makes my now want to start streaming The Pitt) bravely takes on a role even the most seasoned of thespians are reluctant to tackle because of all the pitfalls that most actors, regardless of their station, can fall into headfirst. It usually requires unwavering self-confidence for anyone to play the emotionally tortured Prince of Denmark, but Ball finds a fascinating new accessibility in the character without looking as though his performance is more ego-driven than heartfelt.

His task is aided considerably by O’Hara’s decision to give Hamlet’s familiar soliloquies a freshi innew twist, interspersing Ball’s delivery by alternating passages in echoing voiceovers. It’s as though Hamlet is in a conflicted conversation with his irresolute subconscious and the result is riveting.

Gina Torres is also a major standout as his mother Gertrude, giving a solid weight to the often fanciful and melodramatic ambiance O’Hara adopts in his direction, and Coral Pena adds an exciting street-smartness to her lusty, vaping Ophelia, who at one point sardonically proclaims she has no intention of marrying someone who’s “thirty-something and still a student.”

Hakeem Powell is endearing as the passed-around Horatio (“Everyone’s fucking Horatio,” Ophelia observes), soliciting a collective awwww from the audience when he speculates his relationship with Hamlet seems to be doomed. Fidel Gomez is hilarious as the Gravedigger who constantly corrects his job title as “Groundskeeper and occasionally Gravedigger,” while Ty Molbak and Danny Zuhlke provide more comic relief as Dumb and Dumber-inspired Rosencrantz and Guilenstern.

I would have easily added this ensemble cast to my possibilities for end-of-the-years honors except for the unnecessarily bellowing performance of Ariel Shafir as Claudius and Ramiz Monsef’s slapstick Polonius, which I found indulgent and unwatchable in a Jimmy Fallon sorta way.

There are so many things to praise about O’Hara’s delightfully heretical reinvention, something surely expected for anyone who remembers his Bootycandy or his Tony-nominated direction of the controversial Slave Play a few seasons back.

Here, Hamlet shouts out to Alexa to play music to accompany a rap version of the First Player’s monologue (a showstopping turn by Jaime Lincoln Smith) and when Hamlet is asked as he sits staring at his cellphone, “What do you read, my lord?”, the original “Words, words, words” is again the perfect answer.

I understand how some purists are shocked and offended by Robert O’Hara’s borderline blasphemous vision of one of the most well-known theatrical milestones, but I was all ready for it. Even perhaps the most famous line in any play in the history of theatre is not spared here:

“To be or not to be?” a character sarcastically slams. “That’s not a question… it’s a statement.”

* * *

HIDE & HIDE at the Skylight Theatre

Recently in my review of A Doll’s House, Part 2 at Pasadena Playhouse, I mentioned if asked to name the best of the exciting new generation of playwrights whose work I felt will stand the test of time, Lucas Hnath would definitely be among them. Also high on the list for me would be Roger Q. Mason, a rule-defying and fearless wordsmith I believe is one of the best and boldest theatre artists of our time.

It seems especially clear that Mason could easily be identified as a direct descendant of the innovative and death-defying spirit of Tennessee Williams in his later days—you know, that time when Tenn explored deeply impudent topics and adopted a lyrical style that backfired for him and caused everybody to insist the last century’s best dramatist had lost his touch. I steadfastly then and still believe he was simply way ahead of his time.

I don’t often begin a review by mentioning the work of the director. In this case, however, Jessica Hanna deserves an early shout out. The main influence that turned the critics and the public against Williams was a major career-defining moment in his work which happened just prior to the creation of The Night of the Iguana. It was at that point in his celebrated career that he began his lifelong feud with his great mentor and collaborator, master director Eli Kazan. Without Kazan at his side to help corral so many diverse flashes of thought and the genius of Williams into a cohesive narrative, his plays were all over the place.

Fascinating as their journey may be, I suspect from what I’ve seen that Roger Q. Mason can occasionally get lost in their themes and strikingly contemporary poetry. Like a modernday Kazan, in helming Mason’s Hide & Hide, now in its world premiere at the Skylight, Hanna has proven herself to be the perfect accomplice to help them frame their thoughts and ideas and make it all more accessible. Together, Mason and Hanna are posterchildren for what this kind of electric artistic collaboration can bring to fruition.

Hide & Hide could go sparking off into so many different directions but between Hanna’s inventive staging and the incredibly creative lighting design by Brandon Baruch, Mason’s continuous flashes of genius are both glorified and yet contained in a way that’s as important to the storytelling as the writing itself.

Set in the darkest shadows of Los Angeles’ often harsh Land of Unequal Opportunity in the 1980s, Constanza (Amielynn Abellera) and Billy (Ben Larson) are both newly arrived outsiders to our world of potential plenty, she a bright and educated Filipina here illegally and wary of deportation, he a teenage runaway escaping from a Texas gay conversion camp surviving on the mean streets as a rentboy.

The two meet at the infamous now-defunct Studio One nightclub in West Hollywood and form an unlikely bond, forged from their mutual need to find their individual though highly diverse identities, their universal struggle to be free, and their pursuit of the illusive American Dream—something in 2025 which now sadly seems more an ancient myth than anything attainable except in the rarest of cases.

Their possible quick fix is a shaky one as they enter into a sham marriage that will give Constanza her citizenship and offer Billy some desperately needed stability. It’s a solution that's clearly doomed when viewed by an audience hardened to the facts of life some 45 years in the future and compounded by the dastardly dealings of a destructive ego-maniac intent on destroying our country and banishing the term “Land of the Free” for all time to come.

Abellera is stunning not only as our rapidly crumpling heroine slowly losing all sense of self-worth, but in a series of side characters, including her greedy aunt advising her how to make her fortune as she did by giving up her ideals and as Ricky, a sleazy lawyer and human trafficer who drains everything he can get from Constanza, including her self-respect, and takes advantage of Billy’s youth and any scrap of dignity he has left.