- HOME

- CURRENT REVIEWS

- LADCC SPECIAL ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2025

- TICKETHOLDER AWARDS 2025 - Part One

- TICKETHOLDER AWARDS 2025 - Part Two

- "WAITING FOR WALK"

- TRAVIS MONOLOGUES 2025

- FEATURES & INTERVIEWS

- MUSIC & OUT OF TOWN REVIEWS

- RANTS & RAVINGS

- MEMORIES OF GENIUS

- H.A. EAGLEHART: HIEW'S VIEWS

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 1

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 2

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 3

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 4

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 5

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Collection 6

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Saints & Sinners

- TRAVIS ART FOR SALE - Pet Portraits on Commission

- COMPOSER SONATA: Hershey Felder Portraits

- TRAVIS' ANCIENT & NFS ART

- TRAVIS' PHOTOGRAPHY

- PHOTOS: FINDING MY MUSE

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: WINTER 2025 to... ?

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: WINTER - FALL 2025

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: SUMMER - WINTER 2024

- REVIEW ARCHIVES: FALL 2023 - SPRING 2024

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [1946 - 1996]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [1997 - 2015]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2016 - 2018]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2019 - 2021]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2022 - 2023]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2024 - 2025]

- A LIFE IN PHOTOS [2026 to...

- LA DRAMA CRITICS CIRCLE AWARDS 2024

- TRAVIS' ACTING SITE & DEMO REELS: travismichaelholder.com

- CONTACT THLA

Best Laid Plans of Mice and Flower Children

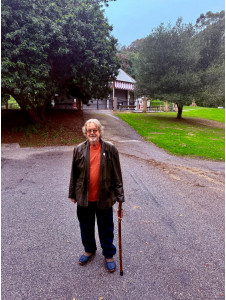

NEW YEAR'S EVE, 2025: We beat the rain for a great Goodbye 2025 hike through Griffith Park and Hugh, who knows all the paths and sights thanks to his many times taking his kids from Griffith Park Boys Camp on marches through the trails, led me to a forgotten place for me that I hadn’t seen in many years but once knew quite well: the now-shuttered Carousel grounds.

I was suitably nostalgic and amazed by the memories that flooded back. In 1967, this was the spot for the now infamous Be-Ins and Love-Ins that brought literally thousands of us “flower children” there to gather, pass the doobies, drop the Clear Light, hear our generation’s great guru Timothy Leary speak, and for the first time listen to the likes of Big Brother, the Dead, Joplin, Neil Young, The Byrds, and many more.

Astonishingly for me, that time 59 years ago was still fresh and clear in my mind. I realized as we walked the same now silent paths that I am probably approaching being one of the last left standing who was lucky enough to experience those magical, hopeful, free-spirited, idyllic times when we thought thanks to us and our collective energy great change was in the air!

1967... and 2025

The Groundlings: Still Getting Salty at 50

In a town where everything seems to disappear and only later be lauded as nostalgia—from restaurants and boutiques and, beyond ‘em all, theatres and theatre complexes—no doubt The Groundlings are something of a phenomenon.

In 1974, the lategreat Gary Austin and a group of 50 actors with a passion for improvised sketch comedy and the teachings of Viola Spolin and Del Close from Chicago’s Second City, banded together to create a safe place where they could work out. The company grew and prospered so quickly the following year they moved into a former decorator’s showroom/gay bar/massage parlor on Melrose just west of Poinsettia and today, a mere half-century later, it’s still their home.

I discovered the Groundlings bigtime in the early ‘80s when no week was complete without downing an amazing amount of good party drugs and heading to the troupe’s nondescript brick-fronted 99-seat theatre every Saturday night at midnight to see the coolest and most trendy of all cult destinations of the era: a live, unrehearsed weekly little event called The Pee-Wee Herman Show.

Starring a then-unknown manchild with an unstoppable imagination named Paul Reubens and supported by his devoted comrades from the Groundlings company, nothing for me was ever more fun or more addictively compelling. I even have a tattoo of Pee-Wee dancing the Frug on my left ankle.

There’s no doubt what wonders Gary Austin’s wild adventure has spawned over the last half-century, including in 1982 the establishment of the Groundlings School of Impovisation which today has an annual enrollment of some 4,200 students from around the world.

Over the years, the Groundlings have nurtured and introduced some of the world’s most impressive comic talent including, besides Reubens and his First Lady Lynne Stewart (Miss Yvonne, the Most Beautiful Woman in Puppetland), Conan O’Brien, Phil Hartman, Jennifer Coolidge, Julia Sweeney, Kathy Griffin, Tracy and Lorraine Newman, Jon Lovitz, Lisa Kudrow, Will Farrell, Kristin Wiig, Joey Arias, Mindy Stirling, Casandra “Elvira” Peterson, Anna Gasteyer, Adam Carolla, Melissa McCarthy, Maya Rudolph, Chris Kattan, and Jimmy Fallon.

Despite its meteoric rise, in the late 1990s the Groundlings’ popularity had begun to somewhat diminish, as everything too often seems to do in the fast paced “Let’s Do Lunch” trajectory of Lost Angeles, and the troupe fell into a period of deep financial crisis. They found themselves unable to pay their lease obligations on their beloved building and were in grave danger of losing it. That’s when my dear friend and former fellow teacher at the New York Film Academy George McGrath stepped in.

George, best known for his Emmy-nominated turns writing and appearing on TV’s Pee-Wee’s Playhouse and Tracy Ulmann’s Tracy Takes All, as well as scripting the cult classic film Big Top Pee-Wee, came up with the perfect idea to keep the theatre open. He created an all-improvised evening of sketch comedy at its best called Your Very Own TV Show, where an unsuspecting audience member was chosen in an onstage casting session to become the star of his own sitcom—which in the second part of the show was taped live and featured plot points shouted out from the crowd during Part One.

Produced by Jeffrey Lane and directed by George and Emmy-nominated writer-producer Judy Chaikin, every performer, musician, and tech person donated their time and worked for free. The show was an instantaneous success, garnering rave reviews and landing a feature on the cover of the LA Times’ Arts & Leisure section. It played to full houses for almost a year and the Groundlings home was saved.

Dubbed “The Show that Saved the Groundlings,” Your Very Own TV Show has been revived many times over the past 35 years and on June 9, 2025, it came back once again, albeit for the very first time without the onstage participation of the brilliant Lynne Stewart, who left us all wanting one of her warm cuddly hugs this past February.

Mounted as a benefit for the Lynne Marie Stewart Memorial Alumni Fund, once again Judy Chaikin directed and George emceed the delightfully inventive and hilarious proceedings featuring Frau Farbissina herself, Mindy Sterling, who over the years has also never missed being a part of the event, and my other cherished pal and former NYFA colleague Suzanne Kent, the Playhouse’s original Real Housewife Mrs. Renee and the creator of the Groundling’s still enduring Sunday Show in 1982.

During the first section of the evening, the performers improvise a writers’ session, where George and Mindy were tapped to be partners (once the writers of Rhoda, we’re told, fired because they insisted on writing only in the shower), meeting in a dry location to brainstorm the concept for a new pilot.

With the audience choosing all details of the script, from the title (here decided to be Get Me the Hell Outta Here! by an audience member who has obviously been on LA awhile) and deciding the leading character would be a young man named Spin who had a thing for schtupping older women and lived at home in Salt Lake City with his devout Mormon parents (Sandy McCree and John Stark).

“Don’t you get salty with me!” was chosen as his frequent catchphrase. You get the idea.

After another tableaux where the writers pitched their concept to network brass (McCree and former NYFA student Reinaldo Garcia), the stage became a casting office run by Jim Wise and Michael Churven, with Stark portraying a grumpy veteran actor called in to read for the coveted leading role.

Two other two chairs placed in the office’s waiting room were reserved for a pair of unsuspecting members of the audience—with Chaikin beginning her search for the Next Big Thing by asking anyone not an actor among those of us gathered to raise a hand.

The pickins’ were decidedly sparse in the obviously Industry-dominated event, but she finally chose two perfect choices. A very game young guy named Barras auditioned with a scene from Joanie Loves Chachi and was cast as Spin, while the other hopeful, a rather Emo Phillips-y nurses’ assistant named Malcolm was chosen as his stunt double soon called up to perform a tongue-a-licious make-out scene with Stirling.

After being subjected to a quick coaching session conducted by Suzanne Kent as the stern Sister Mary (her persona chosen from the name of my friend Kelly Hughes’ first grade teacher) and her bubbly assistant Sarah Baker, poor Barras was ready and willing to take on Hollywood.

By the end of the intermission, an instantly designed logo was unveiled, as well as an entire video “cold open” lead-in sequence to begin the all-new Get Me the Hell Outta Here! pilot featuring Barras and his wildly eclectic supporting cast. Meanwhile Wise, with the participation of accompanist Willie Etra, had created an entire theme song for the series, complete with some very topical lyrics and rather iffy but cleverly groan-able rhymes.

After a scene where the poor western-clad Spin (the audience decided he had a thing for cowboy culture) is caught sneaking out of the house by his strict parents (“Don’t you get salty with me!,” he warns them), our hapless hero does a speed dating session with some rather scary looking potential hook-ups played by Kent, Baker, and finally Sterling as his final choice: a pistol wielding “woman with problems” who changes everything for poor salt-free Spin.

Nearly everyone in every scene was given their own personal assistant, each one played by charismatic future star Patrick Steward, and each one an overly eager character saddled with personality traits supplied by us meanspirited viewers intent on not making it easy for him.

Patrick is another NYFA graduate who in 2016 I had the privilege of mentoring as he ambitiously mounted and directed a smashing soldout international student production of HAIR (in which I royally pissed off our tightassed administration by sneaking in a cameo appearance and song as Margaret Mead). Then as now, the talent and enthusiasm that obviously makes this kid exciting to watch work all but stole the show.

To say this one-of-a-kind night out to see Your Very Own TV Show, also hawked in ads as something “You Can’t See From Your Couch,” could certainly once again become a regular event that just might play another year or more if the participants had the time and energy to put into it.

In the meantime, the ridiculously prolific Groundlings offer one-night and distinctively bonkers sketch comedy performances several times each week and virtually any of them will make you fall apart and leave in complete wonder about what these worldclass comic geniuses are able to accomplish.

Whatever outrageous thing they do, the Groundlings never cease to astound me. I like to think I’m both a good actor and a funny guy, but unfortunately, improv is beyond me. I can think of funny things to do or say whenever I’ve been confronted in my life and career with such an opportunity, but only on about a 30-second delay. I have no idea how these brilliant entertainers manage to do what they do on the spot—it’s a unique skill I’ve coveted all my life but has always eluded me.

No wonder the Groundlings and their uber-popular School of Improvisation have been around and turning out shows and stars on an inspirational continuous loop for 50 years, while so many less enterprising art entities have fallen by the wayside. There’s simply nothing like them or what they do on the planet earth—and if you should disagree, why, don’t you get salty with me, motherfucker!

FOR INFORMATION ON THE GROUNDLING’S SHOWS AND CLASSES: www.groundlings.com

Hershey Felder: In a Category All His Own

Photo courtesy of Hershey Felder, here on tour in Rachmaninoff and the Tsar

American Theatre Magazine once commented that “Hershey Felder, actor, Steinway concert artist, and theatrical creator, is in a category all his own.”

Look up the term overachiever in the dictionary and I wouldn’t be at all surprised if one found a photo of international theatrical innovator and concert pianist phenom, who for over a quarter-century has brought live performances of his solo Composer Sonata series to audiences worldwide.

Writing, designing, appearing as, and performing the enduring compositions of some of the world’s most treasured musical geniuses since his bareboned beginning right here in Los Angeles in 1998, he has created and produced continuous and incredibly memorable productions that have played some 6,000 performances all over the U.S. and as far away as South Korea, with celebrated Broadway and London’s West End stops in between.

In 2020, Hershey was preparing to bring his newest one-person show to Los Angeles, the world premiere of his ambitious Nicholas, Anna & Sergei, documenting the life and musical genius of Sergei Rachmaninoff and something that would prove particularly groundbreaking as he planned to play all three roles: the composer himself as well as Russia’s last Tsar, Nicholas II, and also Anna Anderson, the woman who claimed to be the Grand Duchess Anastasia. Of course, the pandemic dashed plans for that tour but lord knows nothing stops the infectious creative spirit of Hershey Felder.

He returned to his home in Florence, Italy to sit out the international lockdown, but instead of what could be an introspective period sitting on his veranda overlooking one of the world’s greatest cities, Hershey began producing an amazing collection of films. The all-new empire began where the whole thing started, offering a live streaming performance from his home of his first ever project that debuted here when he was a mere prodigy of 25 at the now-bulldozed Tiffany Theatre in WeHo: George Gershwin Alone.

His career skyrocketed back then with his jaw-dropping performance as Gershwin and, for me, it also began a cherished personal friendship that has only grown with time. Besides his unearthly take on Gershwin’s life and art, which went on to play Broadway’s Helen Hayes Theatre and the West End’s Duchess Theatre, Hershey’s phenomenal body of work includes his Monsieur Chopin; Beethoven; Maestro (as Leonard Bernstein long before Bradley Cooper’s film); Franz Liszt in Musik; Lincoln: An American Story; Hershey Felder as Irving Berlin; Claude Debussy: A Paris Love Story; Our Great Tchaikovsky; and Monsieur Chopin—all of which not only presented him onstage playing the composer himself but sitting down at the Steinway to brilliantly perform some of the world’s most indelible music.

Asked once during one of his traditional question-and-answer periods at the end of his performances what made him decide to create a solo piece playing Gershwin in the first place, Hershey’s answer was choice: “Trying to pay the rent.”

Along the way, his own masterful compositions and recordings have included Aliyah, Concerto for Piano and Orchestra; Fairytale, a musical; Les Anges de Paris, Suite for Violin and Piano; Song Settings; Saltimbanques for Piano and Orchestra; Etudes Thematiques for Piano; and An American Story for Actor and Orchestra. He was also the adaptor, director, and designer for the internationally performed play-with-music The Pianist of Willesden Lane with Steinway artist Mona Golabek; producer and designer for the musical Louis and Keely: ‘Live’ at the Sahara, directed by Taylor Hackford; and writer and director for Flying Solo, featuring opera legend Nathan Gunn. He has also operated a full-service production company since 2001 and has been a scholar-in-residence at Harvard University. See? An underachiever for sure, right?

Whatever the reason for becoming one of our time’s most prolific creators and promoters of great art, it was that one humble 99-seat germination at the Tiffany all those years ago that again led to a new direction for his one-man empire during Covid, taking the unstoppable Hershey into that bold new detour into film production. His return as Gershwin, shot live at his Florence villa in the dead of night so it could be seen live here at 5pm on a Sunday afternoon, was pure electricity. This was followed by recreating several other of his mesmerizing globally acclaimed performances, including his turns as Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, Debussy, and Irving Berlin, the last broadcast live from a glorious and historic Florence theatre complete with a surprisingly charming 400-year-old creaking wooden stage floor.

Subsequently, for his newly minted Live from Florence, An Arts Broadcasting Company, he produced a staggering 18 theatrical films, stunningly produced projects that grew beyond the limitations of lavish recreations of his Composer Sonata performances. These included The Assembly; Musical Tales in The Venetian Jewish Ghetto; Chopin and Liszt in Paris; Violetta, the story of Verdi’s Traviata; Dante and Beatrice in Florence; Mozart and Figaro in Vienna; Puccini; Before Fiddler, a musical about and featuring the beloved tales of writer Sholem Aleichem; Great American Songs and the Stories Behind Them; and Leonard Bernstein and the Israel Philharmonic, a documentary.

Perhaps one his most impressive efforts was the reworked film version of the scrapped Nicholas, Anna & Sergei, based on the script he was perfecting to begin touring before the pandemic stopped it cold. Co-directed by Hershey and Italian cinematographer Stefano DeCarli, their highly personalized production was majestically, sumptuously presented, offering a fascinating insight into the tumultuous world of the Russian-born Rachmaninoff, who spent his life mourning his furtive flight from his homeland. In the early 1940s, the terminally-ill composer’s dreams were, as Hershey cleverly invents, haunted by morphine-fueled visions of the ghost of his Tsar as Rachmaninoff laments his life choices, declaring his anger at his ghostly visitor that his work had suffered from Nicholas’ life choices and the horrific deaths of the Romanoff family.

“Melody,” we were told in Hershey’s tale, “abandoned Rachmaninoff when he left Russia for the USA,” where he became a naturalized citizen shortly before his death in 1943 at the age of 69.

There was a hint of redemption in the story when Rachmaninoff met and financially championed Anna Anderson, the former mental patient the world once embraced as possibly being the Grand Duchess Anastasia, who it was said had survived her family’s mass assassination in 1918. He more and more began to question the validity of her story, all of which is admitted to the phantom Nicholas as the composer lies dying at his home in Beverly Hills at 610 N. Elm Drive, the place Rachmaninoff prophisized would be the place where he would die the minute he first laid eyes on it.

There were for me personally definite pros and cons to experiencing Hershey’s musical artistry on film and online. I can’t recommend anyone try to watch it on a cellphone as I did the first time—and I have to thank the fury my initial viewing method elicited from one Mr. Hershey Felder himself, who demanded I watch it again on a bigger screen utilizing a better link he sent. It was great advice, particularly considering the teeny-weeny iPhone-sized subtitles flashed onscreen during the film’s scenes spoken in Russian.

The pros obviously include the sweeping cinematographic images, the detailed costuming, and the employment of some dynamic actors and an amazing full symphony-sized uniformly masked orchestra. Still, the best thing to me was being able to see Hershey’s hands in closeup shots as he masterfully interpreted the music of Rachmaninoff—although I have to admit I did miss hearing the compositions ring out live in a darkened auditorium fitted for excellent sound rather than through my computer’s tinny speakers.

And so nothing could have been more thrilling than Hershey’s return in August, 2024 to the live onstage project, redubbed Rachmaninoff and the Tsar, once again revamped for live presentation and world premiering right here at the Eli and Edythe Broad Stage in Santa Monica before going off to tour the globe like its predecessors. The new home for the artist proved just about perfect, featuring dynamic acoustics I can attest to myself from my time appearing there a few years ago as Cheswick opposite Nancy Travis and the late-great Tim Sampson in Jenny Sullivan’s production of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

The venture was beautifully designed by Hershey, impressively directed by his longtime collaborator Trevor Hay, and blessed with projections designed by DeCarli culled from their film version. More than just marking Hershey’s exciting and long-missed return to live performance in a new piece, it also heralded the first such project written to be performed with another actor rather than just as a solo presentation. Touring with Hershey was noted British-Italian actor Jonathan Silvestri as Tsar Nicholas II, an incredible talent best known to international audiences as Cardinal Fonsalida in HBO’s hit series Borgia.

Hershey and Silvestri played off one another perfectly and left one to understand a very important aspect of both men’s individual stories: their love for family and how that affected their highly divergent but equally passionate trajectories of their lives. Along the way, we also heard of the composer’s mentoring of Anna Anderson—although I would have loved to have seen the great classical chameleon’s original plan to play the character himself come to fruition. I’ll just bet that would have been a sight to see.

Hershey’s lyrical and painstakingly researched script was an arresting part of Rachmaninoff and the Tsar but as usual, magic happened when the master turned to the piano and in detail identified familiar moments in the great man’s work that inspired his dulcet, hypnotic compositions, including his C-sharp minor Prelude to his Piano Concerto No. 2 and his glorious Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini that remain timeless contributions to the history of music.

Proving further that Hershey Felder is either a cyborg or is on something I wish he’d share with me, also in 2024 he was named Artistic Director of the historic Teatro della Signoria in Florence, as well as Teatro Nicollini in his adopted home’s City Center which, he proudly proclaims, possibly in a thinly-veiled effort to get me to visit, has a great view of the ass of Michelangelo’s David. It seems we know one another quite well these days.

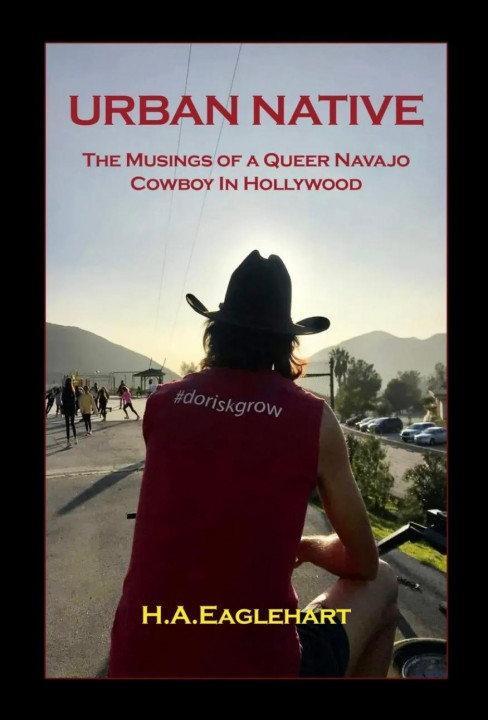

URBAN NATIVE: Forward

by Travis Michael Holder

If there’s anything that might leave someone questioning their skepticism about the possibility of reincarnation, it could be parallels between the legendary Will Rogers and H.A. Eaglehart.

Where the beloved Will was born of mixed race and Native American ancestry on Cherokee Nation land in Oologah, Oklahoma, Hugh was born of mixed race and Native American ancestry 110 year later on Navajo Nation Trust land in Shiprock, New Mexico.

Will dropped out of public school in the 10th grade, beginning his career roping on the rodeo circuit and wrangling horses before making his name in vaudeville and eventually finding his way in Hollywood, while Hugh left public school at his own insistence at a ridiculously early age to be homeschooled and, in his teen years, was competing on the rodeo circuit, spinning ropes, and by his early 20s wrangling horses at Sunset Ranch in Los Angeles’ Griffith Park.

Now, I’m not really suggesting H.A. Eaglehart is the resurrected spirit of America’s greatest storyteller and social commentator, but there’s no denying the similarities. It was while in New York City performing in the Ziegfeld Follies where Will Rogers honed his aw-shucks humor and keen insight about the world as it wobbles on its severely compromised axis, while Hugh arrived in Manhattan on a scholarship to study acting at the New York Film Academy after developing a successful modeling career in New Mexico and the Southwest.

Both were also racing to escape their rigid, demanding, ultraconservative upbringing each recognized was far too much of a dead-end for a bright and ambitious young’un to endure. Growing up realizing his inquisitiveness was not conducive to life and finding acceptance in an insular rural community, Hugh knew he had to beat a hasty retreat. As David Bowie recalled of his own break from a restrictive childhood, “The notion for anyone with an iota of curiosity is to get the hell out of such a place as soon as possible.”

Hugh’s scholarship at NYFA led to a transfer to the school’s west coast campus to obtain his degree the following year, the place where his own quick humor and eagerness to glean knowledge of world affairs he could discuss with tourists from around the world while showing them the sights high above LA from the backs of horses, quickly made him a popular urban cowboy.

Still, it was his first college degree in outdoor education—a degree he worked from age 15 to pay for himself after his father’s disdain for higher education made juggling three jobs while in school fulltime his only option—that resulted in Hugh looking down from horseback on LaBonge Summit above the Hollywood Sign to Griffith Park Boys Camp one day and deciding helping kids grow and prosper and discover themselves was far more important to him than bucking the Hollywood system.

It won’t take you long to fall in love with the guy's homespun wisdom and signature voice when you discover that crossroads where his uncanny inborn Native American spirituality, his folksy insight about life and protecting the dwindling resources of our planet and its children, and his remarkably obvious passion to teach and make the world a better place will leave you wanting to curl up on the couch in front of a cozy fireplace and get to know a truly remarkable human being.

Will Rogers famously once said he never met a man he didn’t like. I’ll bet he would have adored H.A. Eaglehart and realized the future of all the things we hold dear could be in good hands if more people discover what this uniquely brilliant Urban Native has to share with the rest of us.

Back Down in the Valley: The Classic 'Dark of the Moon' Finally Resurfaces as a Bold New Musical

28MAR23: It’s been a long and winding (country) road for Howard Richardson and William Berney’s mysterious and magical classic 1945 “play with music” Dark of the Moon, a once popular piece fallen into obscurity over the years despite many previous well-intentioned efforts to grab the rights and transform it into a full musical.

Among the successful artists who had been turned down through the years by the playwrights’ estate have included Jerome Robbins, Bob Fosse, and Marvin Hamlisch, but they believed no one pitching an adaptation had ever found the heart and strange, gossamer beauty of the tale.

Based on the centuries-old European folk song “The Ballad of Barbara Allen” and set in a small backwoods town deep in the American Appalachians, Dark of the Moon is the story of a “witch-boy” from the Smokey Mountains who descends from the fog to become hopelessly enamored by a beautiful, feisty village girl desperately looking to find herself in the outside world she has never known.

John makes a pact with the spooky “Conjur Woman,” potentially trading his immortality to join his earthbound love on good ol’ terra firma, but it’s a deal that will only become permanent if the lovers can work through the prejudice and fear that haunts their relationship and stay faithful to one another for a year.

It is a poetic, soulful Twilight meets Romeo & Juliet-esque tale which originally included the song upon which it is based, as well as a few authentic old folk songs such as “Down in the Valley” and “Give Me That Old Time Religion.”

Surely, in a world where The Phantom of the Opera and Les Miz could become major contemporary Broadway warhorses, Dark of the Moon seemed to be the quintessential project to adapt into musical theatre, but if Jerry, Bob, and Marvin couldn’t make the grade, it seemed unlikely the play would ever again to be produced professionally.

The fog began to lift on the fictitious village of Buck Creek, however, when noted screenwriter and film producer Jonathan Prince had the inspiration as to how the play could be adapted without losing its heart or watering down its message of the destructive nature of narrow-mindedness and intolerance. The result is the staggeringly ambitious developmental world premiere of Dark of the Moon, A New Musical, now debuting at the celebrated Rubicon Theatre Company in Ventura and playing through April 16, RTC’s 46th mainstage production presented in their ongoing commitment to the creation of new works.

The production is being directed by Rubicon founder and co-Artistic Director James O'Neill, who has shepherded more than 45 world premieres at the theatre since its inception in 1998 and is himself author of Lonesome Traveler, which debuted at RTC before landing off-Broadway and touring extensively featuring such folk giants as Peter Yarrow, Noel Paul Stookey, and George Grove, among others.

Dark of the Moon features an all-new dual bluegrass and rock score by multi-platinum musical hitmakers Lindy Robbins, Dave Bassett, and Steve Robson, and a cast and artistic team of some of the most impressive talent on the planet, including choreography by Christopher Gattelli (Tony winner for Newsies), musical supervision by Brad Haak (conductor of An American in Paris and Mary Poppins on Broadway), musical direction by Brent Crayon, and arrangements by Carole King’s grandson, renowned guitarist-composer Dillon Kondor.

What broke the resolve of the play’s estate? Explains O’Neill: “Elliott Blair, the attorney who represents the estate, was waiting for someone to solve the problems for a contemporary audience. Michael Jackowitz of WitzEnd Productions, Jonathan, and Lindy flew to New York at various times to present their ideas and he has really gotten behind this production and believes in what they are hoping to accomplish.

“The story is timeless… it’s about loving the other,” O’Neill continues. “The original writer was a gay man in the 1940s who felt he couldn’t give voice his own truth and his own story, but he could tell the story of a witch boy falling in love with a rebellious mortal girl, both experiencing different levels of hate and disapproval from their communities.

“Jonathan had the idea for a dual score—folk and bluegrass performed by the townspeople of Buck Creek—and rock and soul performed by the witches. The challenge in telling the story today is that some plot elements had to be changed. In the original story, the spell will be broken if Barbara is untrue and there is a rape in the church. In this story, the writers found a way for Barbara to have agency in the choices and sacrifices she makes. I think Jonathan has done that in an ingenious way.”

“It’s a big undertaking,” adds the Rubicon’s co-Artistic Director Karyl Lynn Burns. “We are so grateful to get to share this beautiful musical story with our audiences and to work with an amazing team. The writers are extraordinary. It’s been a life lesson to see how Jonathan, Lindy, Dave, and Steve work together. They are incredible collaborators. No stepping on eggshells but so much respect and love between them. And they’re facile and fast and so keenly intelligent and tuned in to each other. It’s an honor to be in the room as they finish each other’s sentences and lyrics and musical phrases.

“Going back to big, it’s a cast of 29 and, including our onstage bluegrass band and another live rock-and-roll band downstairs, it’s a company of 34 in our intimate 185-seat space. It’s a rare opportunity.

“Developing new works and creating a nurturing environment for established and aspiring playwrights has always been a fundamental part of our mission and vision at RTC but this is definitely the largest and most ambitious undertaking in Rubicon’s history. We have been involved with the show for over four years through our Plays-in-Progress program and have been working dramaturgically with the team.

“The project came to us through our Director of New Works Michael Jackowitz, who has been with us since 2006 and was the recipient of Rubicon’s first Innovation Award during our 20th anniversary season. He has brought us many amazing projects and has also become a Tony Award-winning Broadway producer himself. He and his partners at WitzEnd Productions, especially Jeffrey Grove, have provided generous support so we are able to produce a story of this scope for our audiences.”

Bookwriter Jonathan Prince is the guy to thank for the idea of turning the play into a musical. Prince, who once turned a serendipitous meeting with George Burns into writing the film 18 Again, has written and produced over 200 hours of television on network, cable, and streamers. Many of his projects have had strong musical themes, including his Emmy-winning NBC series American Dreams, his film 1660 Vine, and music also played a vital role in his multi-year B.E.T. series American Soul, his HBO series Off the Record, and pilots developed with Mick Fleetwood, Stewart Copeland, and Broadway producer Andrew Lippa, with whom he is also developing another stage musical.

His personal connection to Dark of the Moon started “decades ago,” he says, when he played a small role in the play at his high school. There are those traditional folk songs and hymns in Richardson and Berney’s original script and Prince loved the idea of the music helping the story unfold.

“Since then,” he admits, “I haven’t been able to get that show out of my head. It’s the story of a star-crossed romance with a twist. It’s not the woman who has given up everything to be with her male object of adoration—think The Little Mermaid—but instead the genders are reversed.

“Then life got in the way for me. That is, I had to go make a living.” But after his many years writing, producing, and directing for film and television, he was “emboldened” to take the concept to Jackowitz and Grove.

“The idea was to let the music of the show reflect the opposing communities, that is humans and witches standing in for the Capulet and the Montagues. The humans would sing in bluegrass songs and the witches would sing in rock, two distinct sounds that must somehow be melded when the lovers are alone.”

Who could deliver such a score, “songs that were the kind of ‘earworms’” that would inspire the audience to go home singing the melodies? “We invited Lindy, Steve, and Dave to bring their talents to the show and they have taken that great notion planted in the brain of a high school student in the late ‘70s and they have delivered.”

Still, the rights needed to be obtained and the fact that brilliant Broadway minds such as Robbins, Fosse, and Hamlisch had tried and failed was in danger of taking the wind out of the team’s sails. “How could we dare think that we might succeed where those geniuses of the theatre had failed?” Prince continues. “But we pitched the vision with all the story changes proposed and with the unique notion of a dual bluegrass-rock score. We were elated when Elliott Blair said, ‘Go ahead’ and he continues to be an enthusiastic supporter of the musical.”

There had been significant issues with the original script, especially in the current #METOO era. It made Barbara Allen a victim rather than a proactive heroine and it also demonized the church and people of faith, not to mention Prince felt the characters of the witches were underdeveloped. Luckily, he had those ideas of how to make it work and when the team pitched them to Blair, he was thrilled with the profound changes they proposed. “They would make the show much more friendly to contemporary high schools, colleges, and professional companies who have been less inclined to do the play over the last few years because of the issues baked into the original.”

The creation of the piece was also something one could call unique. “Many people during the pandemic learned to bake sourdough bread,” quips Prince. “Many planted herb gardens, some took Zoom yoga classes. Lindy, Dave, and I basically Zoom-created an original musical.

“I wrote an outline with suggestions for song placement and themes, but often the songwriters went ahead and wrote songs before the actual scenes from the book existed. Sometimes songs were written after the scripted preface was ready. And always, always, the team wrote and rewrote. Rewrote scenes and dialogue. Rewrote lyrics and melodies. Rewrote characters. It’s been an incredibly collaborative process that’s been sort of amazing, really.”

One of the most compelling things for me about this project has been hearing about how it was unfolding along the journey from Lindy, a prolific five-time ASCAP Pop Award-honored songwriter credited with over 300 major releases, including Jason Derulo’s worldwide smash “Want to Want Me” and chart-toppers for Demi Lovato, Selena Gomez, Fifth Harmony, Backstreet Boys, Nick Lachey, MKTO, David Guetta, Morgan Evans, Hot Chelle Rae, and the 2006 Disney Song of the Year “Cinderella” from the Cheetah Girls.

Lindy and Jonathan had been friends for many years, meeting as performers in the west coast premiere of Elizabeth Swados’ Runaways. They shared a love of musical theatre and unbeknownst to him, aside from her successful career writing pop songs, she had always dreamed of writing an original musical.

“Way back when I was in the group The Tonics and writing cabaret songs in New York in the 90s,” she recalls, “Michael Jackowitz said to me, ‘One day I’m going to find the right musical for you to do.’ I laughed it off then but little did I know.

“I spent the next 20 years back in LA fulfilling my dream to be a songwriter for mainstream radio and against all odds I succeeded, but I never lost my love for musical theatre, something that dated back to a childhood raised by a father who lived for musicals and the ‘Great American Songbook.’ So when out of the blue I got a call from Michael and Jonathan asking if I wanted to hear about a musical, I was ready for a new challenge. I met Jonathan at the Beverly Glen Deli, he filled me in, and I was instantly intrigued. Something felt right!

“Still, in my world of pop songwriting, it’s always collaborative—two people in a room writing together. I knew I needed a partner who could play instruments since I write lyrics and melody but only play a little piano. This led me to my first collaborator Steve Robson, a well-known and very talented writer-producer who lives in London. We wrote songs for what was Act One at the time, but it’s changed so much since then. Some of those songs remain in some form or another and are integral to the show to this day. Unfortunately, due to some health issues and the difficulty of collaborating across the Pond when the pandemic started, Steve amicably withdrew.

“After much deliberation, the solution hit me like a bunch of magical bricks: Dave Bassett! He and I had worked on pop songs on and off for 20 years and I just knew he was the perfect person to take this to the distance with me. Happily, he said yes. He’s incredibly busy and successful so boy, was I lucky to get him.”

The Grammy-nominated, multi-platinum songwriter and producer Bassett, a guy with more than a dozen #1 hits to his name, could not have been a better choice and he agrees that teaming up has been an exciting process. Both veteran songwriters were used to working in many different musical genres, so the choices they made together and the direction in which they took the score, as Lindy puts it, “happened song by song.”

The collaboration was instant magic. “We would get on Zoom or meet at Dave’s studio and just follow the story and let it be our inspiration. It was new and challenging and so much fun to have a story to tell. It helped a lot that Dave plays every musical instrument and is a producer, so he made instrumental tracks—as did Steve—and we sang most of the parts ourselves. The demos were super helpful throughout the process. We knew we wanted bluegrass and rock but there are many songs that fall somewhere in between.”

Bassett agrees wholeheartedly. “I’ve always prided myself on being a stylistically diverse collaborator able to wear many hats,” he says. “This process has given Lindy and me an opportunity to do just that as the styles are so varied throughout the piece.

“Between the bluegrass and the rock and the singer-songwriter style,” Bassett continues, “we have tried not to stray from the instincts that came natural to us. We knew we had to cater to the story, but we didn’t want to follow musical theatre formulas with our songs but rather approach them as we would work within the pop and rock genres. We truly wanted to write songs that could stand alone.”

“What I didn’t realize,” Lindy adds, “is how much of a collaboration it is between the whole creative team. The producers, the theatre, the director, the choreographer, and for Dave and me, our music supervisor Brad Haak has been a big part of all this for us. I mean, we didn’t even know what a music supervisor was and now I can’t imagine us creating this show without him.

“And reiterating what Jonathan said, I was not used to so much rewriting! Sometimes that has been very difficult but the show gets better and better. Now we need the x-factor of an audience to know where we go from here.”

Like Jonathan Prince, my own enthusiasm about this new journey back into Dark of the Moon also goes back to my own personal—though ancient—connection, having strummed a ukulele and warbled “Down in the Valley” myself playing Barbara Allen’s younger hayseed brother Floyd in Chicago in the early ‘60s when I was 14 or 15 under the direction of the Second City’s celebrated director, the lategreat Ted Liss.

The lingering memory of playing Floyd Allen as a teen is an experience I also share with the Rubicon’s longtime resident company member Joseph Fugua, with whom I worked there and then again at Santa Monica’s Broad Stage Theatre as Cheswick and Harding in Dale Wasserman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest under the direction of Jenny Sullivan.

Time, of course, marches on and Joseph, who has also appeared in 110 in the Shade and Brighton Beach Memoirs at Lincoln Center and received universal praise playing the title role in Hamlet at Rubicon, is now cast as Barbara and Floyd’s father Thomas Allen in this new production, a gift for which he is over the moon—you know, the Dark one.

His thrill being part of this brave new undertaking is palpable. “After 23 years as a RTC company member,” gushes Joseph as only he can gush, “this show feels the most… what? Epic. I’m doing a small, small role that I wanted as badly as I’ve ever wanted any role in my life. I just wanted to be a part of this. Everyone is so gifted. The young cast is amazingly talented and it’s also a marvelous intergenerational company to be part of. This is big league and Jonathan Prince is a genius. What he has solved in presenting the witch-human connection is extraordinary and Jim is doing a superb job as director handling such a huge vehicle.

“And may I say I adore your friend Lindy Robbins and I’m so honored to be working with her,” he continues. “Her song ‘Day Drunk’ has been one of my favorites for a long time. The music in this show is truly exciting. Hit after hit, I predict. It will be the kind of cast album that yung’uns will be using as a “Corner of the Sky”-style audition piece for decades to come. I think we’ve got two prom theme tunes that kids would call “sick” and two or three other songs that will be sung at weddings—gay and straight—for years.

He is also over the Moon (another pun intended) about working with the glorious Jennifer Leigh Warren, a ginormous Los Angeles stage presence who created the role of Crystal in Little Shop of Horrors, as well as appearing in the original Broadway casts of Maria Christine and Big River.

In this production she was playing his wife before an injury in the cast moved her into the pivotal role of the Conjur Woman. “There she was, already in the company and let me just say JLW is as fierce as fuck.”

The fierce Ms. Warren also says she is “thrilled to be part of the birthing process creating a new musical again.”

This remarkably talented group of artists, linked together to spark this bold new take on Dark of the Moon into life by tapping into the sheer wonder of their communal energy and devotion to the material, all seem to have one thing in common: a passionate appreciation for the adventure. This phenomenon is obviously foremost of the minds of everyone involved.

“I agree it takes a collaboration of artists working diligently with no rest,” Jennifer Warren quips, tongue firmly in cheek. “It can be exhilarating and frustrating and scary, but in the end it’s incredibly rewarding. I look forward to where this new show goes… hopefully with me included!”

Accompanied onstage by the Ventura County bluegrass band Whole Hog and that rock-and-roll pit band, the massive cast stars newcomer Ava Delaney, a recent graduate of The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama in London and Jake David Smith (Frozen on Broadway) as the star-crossed lovers Barbara Allen and her witch-boy John.

Other veteran performers include Timothy Warmen (Broadway’s Spider-Man: Turn Off The Dark, Jekyll and Hyde, and Steel Pier), Olivier Award-winner Lesli Margherita (Zorro the Musical in the West End, Matilda the Musical and Dames at Sea on Broadway),

Juliette Redden (Anne of Green Gables at Goodspeed), Dylan Goike (Anne Frank off-Broadway), Teri Bibb (seven years as Christine in The Phantom of the Opera on Broadway and on tour), Jane Macfie (Long Day’s Journey Into Night and Ah Wilderness! on Broadway), and Phillip Attmore (Hello, Dolly!, Shuffle Along..., On the 20th Century and After Midnight on Broadway).

The ensemble also features CJ Cruz, Anna Demaria, Heather Youmans, Trevor Wheetmam, Sylvie Davidson, Marc Cardiff, Michael Allen Deni, Michael Stone Forrest, Ximena Valentina Alvear, Madeline Marquis, Lauralyn McClelland, Mark C. Reis, Spencer Ty, and the youngest member of the cast, 12-year-old Anastacia Noelle Jones, daughter of renowned singer Stacy Francis. All I can think of is how our cast half this size squeezed into the Rubicon’s three small dressing rooms during Cuckoo’s Nest. I’ll bet this production will make a lot of close friends.

“In our small space,” Jim O’Neill adds, “those 29 performances by some of today’s best musical theatre artists will be magical—and we also have some fantastical projections and lighting design by Andrew Schmedake, a great set by Mike Billings, sound by Jonathan Burke, and Pamela Shaw’s costumes.”

Still, the magic inherent in the show will require some suspension of disbelief,” he admits. “Not only is the musical itself a huge undertaking but the magical elements of the production have been a challenge as well. We won’t have witches flying, for example, which might be the case in subsequent productions. For us in this developmental process, it has been about discovering what the magic might be for future productions.

"It has been an enormous privilege and the dream of a lifetime to work on this piece. I have always had a great love of bluegrass and folk music and I’ve always been deeply interested in mythology. This musical is very elemental and steeped in mythology. Our cast and the entire creative team have come up with some surprises and the score is thrilling. I think audiences will jump out of their chairs. We can’t wait to see how they will respond.”

CHITA RIVERA: SOMEWHERE IN AN ATTIC A PORTRAIT IS REALLY GOING TO HELL

SPRING, 2018: Somewhere in the darkest, dustiest corner in the attic of some deteriorating old Victorian mansion on some traditionally gloomy moor, there must be a hidden portrait of Chita Rivera that’s really going to hell. Oscar Wilde himself would be impressed.

It was 1960 when I first met Chita, during the time I squeezed my fine young ass into bright orange jeans and started asking Mrs. Garfein eight times a week if Charity was home from school yet. It was a bit intimidating stepping into a huge hit show where a bunch of precocious kids my age had already bonded bigtime, but one person immediately made me feel at home: Chita Rivera, the star of the friggin’ show.

I was 13 then and Chita was 26. I thought she was the oldest person in the world—or at least the oldest person in the world who treated me as a friend and a contemporary despite my age. Still, you see, almost six decades later, something Twilight Zone-y has occurred here: Chit is now younger than I am. She frequently turns her classic profile to one side, noting with pride that she’s been alive so long “I face the wind now.”

A long-overdue reunion in May, 2018, during her brief one-night appearance at the Wallis Annenberg Performing Arts Center in those illustrious Hills of Beverly, proved to be another indelible evening of time-defying brilliance as Broadway’s most unstoppable superstar gifted us once again with her spirit, her energy, her razorsharp humor, and her unique ability to defy the laws of gravity—let alone nature. At 84, perhaps her legendary extension doesn’t quite bump against the side of her head any longer but, as she noted from the Wallis’ Bram Goldsmith stage last Thursday, “as long as it’s sharp, it doesn’t matter.” Sure, there were one or two of her early signature dance contortions Chit admitted she would no longer attempt, quipping that if she did, we could all go home and forevermore be able to say we were right there the night she died.

Chita offered yet another of many memorable evenings in my lifetime being awed by this remarkable woman. Beginning with one of the catchiest tunes from Bye Bye Birdie, “Got a Lot of Livin’ to Do,” those 58 years came flooding back—and I’m sure that must have gone double for another former fellow resident of Sweet Apple, Ohio in attendance: Susan Watson, our original Kim McAfee, who sang “Livin’” to Dick Gautier’s Conrad Birdie nightly for the show’s entire New York run.

The evening shifted from Chit and host/accompanist Seth Rudetsky lounging in adjoining easychairs reminiscing about her long career to stepping back to the piano to perform the actual songs from the celebrated shows that energized her career. From Birdie’s seldom-performed opening tune “English Teacher,” the last notes of which made me want to run onstage on cue and start wailing about going steady for good, the amazingly prolific Chita Rivera Songbook was explored decade by decade, surely causing any diehard musical theatre fan in the audience to experience some kind of collective cerebral orgasm.

There were numbers recreated from her two Tony Award-winning performances in The Rink and Kiss of the Spider Woman, as well as highlights from her many other celebrated appearances, including her last of eight other nominated turns in The Visit. Without much surprise, however, the songs bringing the house down more than any other were from her first New York performance as the original Anita in West Side Story (“A Boy Like That” and a charming recreation of “America” with Rudetsky trying gamely to sing the Bernardo lines) and Velma in Chicago (“All That Jazz” and another hilarious though ill-cast duet of “Class”).

In the interspersed chats, Chit talked about her fascinating days hangin’ and being mentored by guys named John and Fred (Kander and Ebb, of course), Lenny (Bernstein), Bob (Fosse), and Jerry (Robbins), defending her name-dropping to Rudetsky by evoking her impressive longevity: “At my age, I call everybody by their first names because I can.”

She recalled the day at age 15 when some guy sitting in on Dolores Conchita Figueroa del Rivero’s ballet class in her native Washington, DC showed an interest and offered her a scholarship to come to New York to study with him. She had no idea at the time who the gentleman was, but her first great admirer was none other than George Balanchine. When a classmate at his School of American Ballet named Helen begged her to go to an open call for the national tour of Call Me Madam for moral support, Chit tagged along and, having no fear of auditioning, she joined the hopefuls gathering to be seen. She had never acted before and had no idea she could sing but regardless, she was the one who was hired and Helen was not (“And I have no idea what became of her,” Chita recalls with a tad of amused guilt).

The evening ended with a hard to beat finale, performing—compete with cane and top hat—the final showstopping duo she and Gwen Verdon shared nightly in Chicago some 40-plus years ago. Recreating Fosse’s incredible choreography and magnificently imitating Verdon’s famous quavering vocal style in Roxie’s solo sections, she aced “Nowadays / Hot Honey Rag” as an inspiring homage to the lategreat Mr. and once-Mrs. Fosse.

There is no way to truly describe this ageless human dynamo because there’s no one else quite like her. Even in her second of two grueling shows at the Wallis that one night, she faced her guests for hugs and cheer well into the night—providing an opportunity to hear the same thing she’s said every time I’ve been in her presence for nearly 60 years: “How could I ever forget that sweet face?” For me, of course, the feeling is mutual but also easier to express. It’s that portrait in the attic thing, I’m sure.

Chit’s advice to staying youthful and vital well beyond the time when most people are sitting at home knitting and watching HGTV? She does knee-raises every day while she’s drinking her morning coffee. “If the leg goes up,” she explains with a laugh, “you know you have a little more time.”

So, I'm going to start doing my own morning knee-raises while nursing my everpresent pot of Cafe duMonde. If for no other reason, I still need a little more time with Chita Rivera.

JONI MITCHELL: AN ARTIST 'DERAILED BY CIRCUMSTANCE'

Watercoler by Travis Michael Holder

For Salon City Magazine, Oct-Nov 08 / CLEF NOTES by Travis Michael Holder

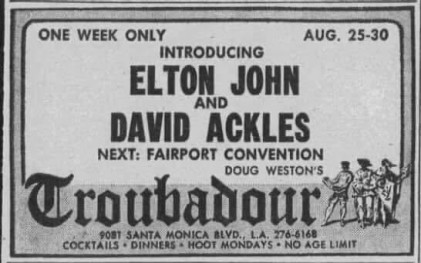

It was about three thousand years ago when, as Talent Coordinator of LA’s infamous Troubadour folk-rock club during the peak of its golden years in the late 60s and early 70s, I was responsible for finding and booking raw undiscovered talent. I was tipped by the manager of a friend that I had to check out his newest client, a reserved Saskatchewan protégé of David Crosby who sang her own tunes and played her acoustic guitar some Sundays in the backroom of McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica.

Although I loved my Sunday afternoons spent as far away from the music scene as I could possibly manage, I reluctantly folded up my towel early, shook out the Venice Beach sand, and puffed on a little inspiration as I headed east up Pico to McCabe’s. The small gaggle of already ardent fans gathered there was beginning to collectively shift on the impromptu club’s unmerciful folding chairs when an ethereal, hesitant lass in her early 20s stealthily made her way to the stage.

Peeking out warily from beneath exaggerated bangs cut into long, gravity-challenged blonde hair, on first impression this bashful flowerchild seemed an unlikely candidate for musical stardom to me, but as she quietly launched into the first bars of “Song to a Seagull,” the readjusting of uncomfortable backsides against metal stopped, replaced by stunned attentive silence and, if I myself was any indication, a few dropped jaws.

During my tenure at the Troub I received close to a hundred demo tapes each week and sat through the sets of many, many hopeful performers with drastically varying degrees of aptitude who waited—sometimes overnight—to sign up for our über-popular amateur “Hoot Night,” which took over the stage each Monday evening at the club. I had learned one thing from those windmill chasers determined to poke their heads above the surface in the shark-filled waters of the music business: there are a lot of talented people out there, but only a few courageous enough to try something new.

Innovation had become the key to getting my attention, the ability to create something different from the standard fare that had made successes of the current crop of superstars. Sitting that night in McCabe’s, I knew this shy young Canadian playing her sad little guitar a few feet in front of me had that quality in spades.

Not long after, Roberta Joan Anderson came to play the Troubadour for the first time and, as they say, the rest is history. I learned right then and there to trust my friends, especially since it was the late-great Laura Nyro who turned me on to Miss Anderson’s music and the manager both groundbreaking music business icons were prophetically to share was David Geffen.

Although Roberta Anderson had set out in life to be a painter, the distinctive style and immeasurably unique gifts she exhibited as a singer and songwriter were to be the stuff of which legends are shaped. The career-interrupted kid who’d begun her musical journey busking on the streets of Toronto to augment her income while trudging through art school—and who had so quickly managed to mesmerize me in McCabe’s backroom that fateful night—soon became one of the most influential musical geniuses of the 20th century: the inimitable Joni Mitchell.

Joni’s first appearance at the Troub signaled the beginning of a remarkable career that has now spanned 40 years, her 21 albums to date winning nine Grammys and seven additional nominations between 1969 and this year, including their Lifetime Achievement Award in 2002. In the 1990s, she was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and chosen fourth on VH-1’s list of “The One Hundred Most Important Women in Rock.” Last year, the face of demure little Roberta Joan from the farming province of Saskatoon, Alberta, graced a Canadian postage stamp.

Joni’s 1971 album Blue, listed by Time Magazine as among the “All-Time 100 Albums,” instantly makes me reminisce about our youthful days when she would barrel into my office at the Troub in a “state” as she looked for her erring ex-beau David Blue, whose dubious inspiration may be the reason that album is regarded as a culmination of her earliest message to the masses: a disheartened view of the world juxtaposed with a fervent belief in the redemptive power of romantic love.

This rather amuses Joni these days from her tranquil media-shunning existence on her secluded country estate near Halfmoon Bay, somewhere north of Vancouver on British Columbia’s gorgeous Sunshine Coast. “At that period of my life,” she admits freely looking back on our action-packed younger days, “I had no personal defenses. I felt like a cellophane wrapper on a pack of cigarettes. I felt like I had absolutely no secrets from the world and I couldn’t pretend in my life to be strong.”

But Joni has proven both strong and uncompromising throughout her career. At the height of her success, she took a drastic turn from reigning folk-pop goddess to concentrate on jazz and blues. The first of her boldly noncommercial explorations into experimental music was 1975’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns, which Rolling Stone was reported to have dubbed the “Worst Album of the Year.” In truth, it was noted by the magazine only as the year's worst album title, but the publicity didn’t help the already contentious relationship between Joni and Rolling Stone, initiated when an earlier issue featured a “tree” illustrating all of her alleged romantic partners, something Joni admits “hurt my feelings terribly at the time.”

Still, Joni has survived intolerance for her musical and personal experimentation over the years and doesn’t care much anymore what critics say. Perhaps a lot of this is due to the fact she’s always considered herself a “painter first and a musician second,” evidenced by continuous gallery and festival exhibitions of her work, as well as the fact she has created the art for many of her own album covers.

Obviously, Joni paints exactly as she creates music, saying both mediums “involve putting down layers until something fully formed emerges.” Her passion here, too, is obvious: “You do your preliminary sketch, you build your skeleton,” she carefully explains, “then you start overdubbing an additional area. You put your first mark on your canvass. It’s the same way you lay your first bed whatever it might be, a drum part or bass part. It’s exactly the same process.”

Joni easily and unapologetically confesses she’s always thought of herself as a fine artist “derailed by circumstance” in her amazingly successful life, even during the peak of worldwide musical fame. “I’m really a painter at heart and I can say this now. Music was a hobby for me at art school, but art was serious. Art was always what I was going to do.”

Joni’s paintings, which seem influenced in equal parts by Matisse and Gauguin—with a hint of the folksiness and humor of Grandma Moses thrown in—have been exhibited in galleries in the States, Tokyo, London, and Canada. In the last couple of years, she has switched media, creating fascinating collage constructions from photographs, including many of her own. A series of enormous photographic panels she calls her “Green Flag Song” debuted in a West Hollywood gallery last year and traveled this summer to the Galway Arts Festival immediately following its mounting at Luminato 2008 as part of the recent Toronto Festival of Arts and Creativity. The annual event also presented the return of Alberta Ballet’s celebrated The Fiddle and the Drum, the much-heralded anti-war dance performance piece created around Joni’s music that premiered last February in Calgary and Edmonton.

A longtime environmental and political activist, with both The Fiddle and the Drum and “Green Flag Song,” Joni has completed a stunning lasting statement about the consequences of war and the prevailing human condition as she sees it, creating a poetic visual dialogue on humanity’s struggle with itself. “Green Flag” utilizes photographic images familiar in our saturated media, which she twists to mock the reactions they’re meant to induce, presenting them instead as evidence of what she sees as the “nightmarish realities of the world we live in.” This signature body of work protests the skewed power of political entitlement as it cries out about our current national and global mess born from aggression and fear.

As usual, Joni has offered contemporary society a gentle yet fervent wake-up call with her art. Her activism has never wavered over the course of the past four decades, but it has shouted its loudest in recent years. She considers Shine, her 2007 album clearly reflecting her social and theological consciousness, as well as presenting a heartfelt plea for the health of the planet, to be “as serious a work as I’ve ever done.” This sentiment was surely strengthened earlier this year when the song “One Week Last Summer” from Shine afforded Joni her fourth Grammy, this time for Best Pop Instrumental Performance of the Year.

Not bad for someone who announced not too many years ago that she was retiring from the music business, eh? Joni explains her indecisiveness with a laugh: “There’s a certain kind of restlessness that many artists are cursed or blessed with, depending on how you look at it. Craving change, craving growth, seeing always room for improvement in your work.”

Martha Graham expressed it best in a letter written many years ago to Agnes deMille: “There is a vitality, a life force, a quickening that is translated through you into action… Keep the channel open. No artist is pleased. There is no satisfaction whatever at any time. There is only a queer, divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others.”

That declaration reinforces everything that makes Joni Mitchell a great artist, something that will be reflected for posterity in her music, in her paintings, in her photographic constructions. It’s an ongoing process of invention for her and, luckily for the world around her, her restlessness—be it a curse or a blessing—continues to enrich us all.

For GORGEOUS Magazine, MAY/JUNE 2009:

Click on link below for PDF:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B3-i2Jd103B3MzQyMEljZGpIMUE/view?usp=sharing

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS' DUELING DIVAS HIT THE BIG EASY... HARD

Travis Michael Holder and Karen Kondazian in The Milk Train Doesn't Stop Here Anymore

For Entertainment Today, 24 APR 08

Having just returned from my third spring journey traveling to the incredible Crescent City to perform at and attend the annual Tennessee Williams / New Orleans Literary Festival, my head is full of dizzying pictures and my poor ol’ body is completely exhausted, sufficiently debauched, and probably about 20 lbs. heavier. Still, I’m artistically refreshed and ready to return again as soon as possible.

This year at the 22nd annual TennFest, my dear friend Karen Kondazian and I had the honor to reprise our roles in last fall’s award-winning Fountain Theatre production of Tennessee’s 1963 flop The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore, a highly successful revival which won director Simon Levy a Garland Award in March, garnered Shon LeBlanc an LADCC Award for his spectacular costuming, and netted Karen a Best Actress nomination from LA Weekly.

Dubbing our event A Witch and a Bitch, we presented our scenes together from Milk Train at the historic Le Petit Theatre du Vieux Carre, located right on Jackson Square in the French Quarter and about two doors away from the St. Peter Street flat where Williams wrote A Streetcar Named Desire. Karen again bellowed her best Williams’ southern diva demands as the dying Flora Goforth, one of the world’s richest women, and I once again donned my best LeBlanc cross-dressing finery as the Marchesa Constance Ridgeway-Condotti, better known on the Italian Riviera as the Witch of Capri. Thanks to the generosity and ingenuity of David Cuthbert, N’awlins premier theatre writer for the city’s daily Times-Picayune, we were joined onstage by local actor Marshall Harris, who gamely stepped in (and out of his clothes) for us as our Christopher Flanders, the character Williams ominously nicknamed The Angel of Death.

It was an amazing year for my third appearance at Le Petit, where in 2003 I had the honor to play Williams himself in another transplant from here, the Laurelgrove Theatre’s original production Lament for the Moths, a piece culled from the great writer's mesmerizing but obscure poetry, and where last year I joined Williams scholar Dr. Kenneth Holditch, Louise Shaffer, and my friends Annette Cardona and Jeremy Lawrence for An Ode to Tennessee.

The newly refurbished Muriel’s Cabaret at Le Petit filled to capacity with Williams fans for A Witch and a Bitch, most everyone staying on after our performances to participate in a lively question-and-answer conversation with Karen and I talking about our own personal experiences knowing and working with Williams, and also discussing the pitfalls of performing Milk Train, one of Tennessee’s most difficult and infamously troubled “later” plays. We tried valiantly to give some insight about how the über-talented Simon Levy strived to make the play relevant for 21st century theatregoers—especially in LA, a city where audiences seem to have a collected attention span landing somewhere between the 101 and the 405.

Among the participants and attendees at this year’s Fest were Terrence McNally, one of America’s greatest playwrights; columnist and terminal Williams aficionado Rex Reed; Tony-winning producer-director Gregory Mosher, who directed Williams’ last full-length play, A House Not Meant to Stand, at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre in 1982; David Kaplan, author of Tennessee Williams in Provincetown and artistic director of Provincetown’s own annual Williams Festival; Erma Duricko of New York City’s celebrated Williams-led Blue Roses Theatre Company; Thomas Keith of New Directions, editor and champion of latter-day Williams works; and Mitch Douglas, the playwright’s last agent, a man who must have had the patience of a saint.

Los Angeles was well represented this year, with two of our town’s preeminent theatre artists in attendance, director Jenny Sullivan and playwright Tom Jacobson, as well as LA’s best stage manager, Andrea “Ando” Iovino, in N’awlins to visit her sister and soon tagged to work at the Fest. Beloved, hardworking and incredibly talented local actor Stephanie Zimbalist of Remington Steele fame joined Reed, former LA actor/playwright Jeremy Lawrence, and Broadway legend Marion Seldes to appear in TennFest’s opening night gala, offering mesmerizing staged readings of Williams’ one-acts Steps Must Be Gentle and This Property is Condemned.

Seldes, who appeared as Mrs. Goforth’s secretary Blackie in the original Milk Train opposite Tallulah Bankhead, Tab Hunter as the Angel and Ruth Ford in my role, also graciously offered insight and humor in a post-performance “talk” with Reed that first night, discussing her career in general and what made Milk Train in particular close after only five performances. After trying to convince Karen and me—with no really clear assurance that she believed it herself—that she had just turned 80 (“Eighty is the new forty,” she quipped), Seldes graciously stayed on for another seminar led by McNally the following day in the ballroom of the Bourbon Orleans, where the next day McNally and Greg Mosher sat to discuss the state of Broadway and the American stage.

Mosher, who won a well-deserved Tony for directing the original Glengarry Glen Ross—and seemed a tad incredulous when I mentioned I’d played Shelly “The Machine” Levene in that play last fall at the same time as I was alternating at the Fountain as the Witch in Milk Train—came up with this year’s best quote from any TennFest event: “Theater is a funny word,” he told his rapt audience. “It refers to a building, it refers to an idea, it’s the way a culture understands itself. Playwrights help us understand who we are. By nature they’re outsiders and their attitude is, ‘I have a story to tell and by God, you're going to listen.’ Producers must step up and make the voices of young playwrights heard.” From your mouth to the Nederlanders’ ears, kind sir.

The now New York-based Jeremy Lawrence, who last year at TennFest offered a preview of his second amazing self-created solo performance as Williams, Everyone Expects Me to Write Another Streetcar (the first, Talking Tennessee, also debuted in Studio City at the Laurelgrove in 2002 in rep with Lament for the Moths), returned to present his newest work again fully realized and even more fascinating than before. Wrote David Cuthbert in the Times-Picayune: “Lawrence inhabits the role of the aging playwright wittily and wondrously. He is wildly funny, authentically moving, and his rapport with the audience is a marvel.”

And while we’re off in braggadocio mode, here’s what Mr. Cuthbert had to say about A Witch and a Bitch: “As two rich, ailing harpies waiting for the other to croak, Milk Train featured the exotic, larger-than-life Karen Kondazian as Goforth, laying on a thick Georgian accent and exhibiting remarkable pectoral control, and Travis Michael Holder as the cross-dressed Witch of Capri, a sly, malicious performance.”

The Annual Stella and Stanley Shouting Contest, affectionately know around TennFest as the “Stell-Off,” is held each year right in front of St. Louis Cathedral in the middle of Jackson Square on the last day of TennFest. It proved to also be a major event this time around, featuring its first ever silent mime finalist and heralding the spirited win of touring Aspen Sante Fe Ballet Company ensemble member Nolan DeMarco McGahan, who swept the judges off their feet after just finishing dancing in his company’s final visiting performance at Tulane University’s Dixon Hall. As I surmised in print last year, I am now even more convinced the best way to win this event is not just to shriek your best “Stell-AAAAAAAAA!,” but to rip off your Brando-blessed white t-shirt as your finale. Works every time—especially if you have a dancer’s body tucked away under your soon-to-be discarded Fruit of the Loom classic.

Now, if you have any aspirations to attempt sporting that dancer’s bod, the only thing you could possibly do in this city, where all good southern-fried New Orleanians laugh uproariously at the word “diet,” is simply to fast while you’re there. Among all the world-class eateries and greasyspoons in the world, this city has some of the best of both. From professional athlete-sized portions of fresh seafood at Jack Dempsey’s in the Bywater to the Camellia Grill at “river’s bend,” where the St. Charles Avenue streetcar meets the levee at the Mississippi, the food here is pure ambrosia.

There’s that trio of Tennessee’s own favorite world-famous and even historic hangouts where you can overindulge: Galatoire’s, Court of the Two Sisters, and Arnaud’s, as well as Irene’s on St. Philip for the best Creole spin on Italian food you could possibly imagine; the Basil Leaf on South Carrollton, the only Thai restaurant where you’ll ever taste a crawdad eggroll, I suspect; the renowned Acme Oyster House on Iberville, where I always go each trip for their knockout seafood gumbo and a massive plate of chargrilled oysters covered in seasoned garlic butter and crusty romano cheese; Café Du Monde for their deliciously bitter chicory coffee and a lapful of powdered sugar plummeting uncontrollably from their signature beignets; and Nardo’s Trattoria in the Garden District, the place to savor a Pinot Noir-infused veal chop topped with boursin, prosciutto, portabella mushrooms and artichokes.

This trip my dear pals Penny Stallings and her husband Barry Secunda, Angelenos who live in N’awlins part of the year, gave Karen and me a dining tour to rival anything seen in Marco Ferreri’s 1973 gluttonous film masterpiece La Grande Bouffe. Among my favorite treats were the fried alligator with chili-garlic aioli appetizer and bacon-fried oyster entrée sandwich at the very reasonably priced Cochon in the warehouse district, the grilled pork porterhouse with brown sugar sweet potatoes and toasted pecans at Emeril LaGasse’s NOLA on St. Louis (near Napoleon’s house on Chartres), lemongrass scallops with coconut-lime broth and roasted eggplant at Susan Spicer’s Bayona on Rue Dauphine, and the layered bluecheese and fig cheesecake-like appetizer at EAT near our Biscuit Palace on Dumaine. Good lord, I swear I’m still full.

Beyond our depraved gastronomical excesses, the highlight of any trip to attend or work at TennFest will always be the privilege to wander around experiencing the sights, the sounds, the food, the music, and above all the history of this mysterious, unearthly city. This year, the fun was doubled by the fact that Karen—the consummate Williams heroine—had never been to New Orleans and had decided to join me this year before we were set to participate as actors. We stayed in the heart of the Quarter at an incredible guesthouse known as the Biscuit Palace, a former 1820s Creole mansion on Dumaine Street about two blocks from Tennessee’s last home in his favorite city and right next to Druid priest John T. Martin’s notorious Voodoo Museum, residence of my friend Jolie Blonde, the world’s most affectionate python.

Originally the home and law office of Christian Rosaleus, founder of Tulane’s School of Law, this amazingly atmospheric small hotel has retained all of its original architectural detail, unobtrusively enhanced by the Biscuit Palace’s equally atmospheric owner Clayton Boyer in the early 1980s to accommodate all the modern conveniences without sacrificing any of the place’s Old World charm and environment. Karen and I were given the adjoining Bourbon and Royal suites, sharing a grand N’awlins-style balcony that overlooked the Mississippi on one side and down Dumaine to Louis Armstrong Park (originally Congo Square, where owners took their slaves on Sunday afternoons to dance and play their forbidden drums once a week only under their dubious supervision) on the other.

My suite was the original “gentlemen’s parlor” of the house, the place where Rosaleus and his friend General William Tecumseh Sherman drank brandy and snorted cocaine, which is ironic since the Biscuit Palace was later utilized as a hospital during the Civil War while Sherman was setting fire to Atlanta. Clayton announced to me proudly the room was also where Clint Eastwood got a blowjob in the movie Tightrope, but I told him it must be my age or the burnout of my randy early years, because at this stage of my life, I was more excited about the brandy and blow than I was about the prospect of getting a Lewinsky. O, the ravages and revenges of time!

After spending a non-stop few days trying to catch every other beguiling TennFest event and cocktail reception we could squeeze in around performing in A Witch and a Bitch, Karen and I gamely shook off our exhaustion and hangovers to join one of Dr. Kenneth Holditch’s remarkable Tennessee Williams Historic Walking Tours through the Vieux Carre. Dr. Holditch, author of Tennessee Williams and the South and a dear friend-hyphen-drinking buddy of Tenn’s (who also still holds his Sazeracs splendidly, I hear), has created the quintessential tour, visiting all the various flats and restaurants and bars where the master American wordsmith hung his many hats over the years. It’s as though Williams has almost replaced Marie Laveau as the most intriguing dearly departed denizen of New Orleans and truly, his spirit is everywhere you look in the French Quarter.